The Spirit of '76

Disruption, Struggle & Formation

The general theme of the 18th century was one of disruption and struggle for almost everyone living at the time. In turn, this led to the formation of how we understand our lives today. The United States’ modern ideals and its own pitfalls can be traced back to this formative century.

For most of the 18th century, both English settlers and Wabanaki people who lived in Maine found themselves in a state of continual siege. At least seven wars took place here in New England, each of which spanned years at a time. Can you imagine what life must have been like? Fear of the unknown only fueled the fighting. Only larger seaports (for instance, Boston, Salem, Portsmouth, or Kittery) received sufficient security through military expenditures from England. France and England, among others, continually fought over control of North America and war was a common fear in this region for almost the entirety of the 18th century.

The 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth halted hostilities between European nations and brought peace to the Maine frontier. Steadily, English colonists rebuilt forts into central Maine, where many Wabanaki had taken refuge from the embattled southern areas. Their safety in this central area now became more tenuous, too.

Over the next 70+ years, Massachusetts became more and more estranged from its own “colony,” the District of Maine, as in that same period of time it declared war on the Wabanaki several times. That, in addition to the European wars fought in the same decades, wore down even the strongest people.

All the while, European settlers here in the village of Kennebunk started an economy that this town still benefits from today. It was a century that had many different answers to the united request for freedom.

SHIPBUILDING EMERGES

By the first decades of the eighteenth century, shipbuilding emerged as an industry in Kennebunk. As early as 1719, a few enterprising European settlers had built their own sloops and two-mastered schooners to transport local goods. The earliest vessels that transported the most lucrative commodity, lumber, were not yet built or owned locally. These ships came from points south to pick up lumber from the lower reaches of the Kennebunk and Mousam Rivers to be shipped abroad. Shipbuilding was not firmly established in the Kennebunks until the end of the Seven Years’ War (the North American part o the conflict was called the “French and Indian War”) in 1760. Only a few vessels were built on the Kennebunk River before the start of the Revoluntionary War (1776), but shipbuilding on the Mousam River started by 1773.

John Bourne (1759-1825)

LARRABEE’S GARRISON (1714-1727)

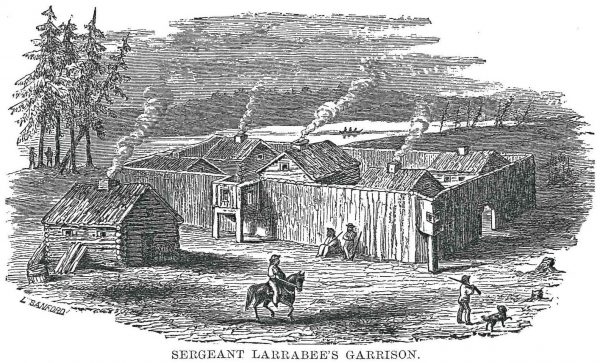

Considered one of the first European settlements in Kennebunk, William Larrabee built a small house on the eastern bank of the Mousam River in 1714. It was eventually enclosed by a large palisade and came to be known as the Larrabee Garrison. It covered about an acre of ground with walls built out of large lumber about 14 feet high. After William’s death in 1727 his son, Sergeant Stephen Larrabee, inherited the Garrison. Over time it expanded to include five houses.

There were several Garrisons in the area of Kennebunk and Wells that early European settlers built to protect settlements from clashes with local Wabanaki, arising from land disputes. The 18th century was marked by a series of conflicts between indigenous tribes and European settlers, flaring from disputes over control of land and resources. Some of these disputes stemmed from the numerous wars between France, Spain and Great Britain over control of the American colonies.

In addition to watching an influx of settlers into the lands on which they lived, the Wabanaki people experienced incredible suffering from new diseases brought by these first settlers; in addition to trading abuses, land grabs and enslavement.

A marker near the site of the Larrabee Garrison can be found on the Bridle Path. Though it is not clear how long the Larrabee Garrison was occupied, historical records indicate until at least 1747.

PERMANENT SETTLEMENT ESTABLISHED

In 1760, more than a century after John Sanders first settled near the coast, there were an estimated 80 families in the village of Kennebunk. At least two sawmills operated in the village and citizens had established their first meeting house.

In every New England town, the colonial meeting house was a focal point of the community, a place not only for religious worship but also to discuss town business and political issues. In 1750, the residents of the village of Kennebunk (at that time a section of the town of Wells), weary from traveling to Wells Center (seven miles away) to attend the First Congregational Parish of Wells, founded their own parish, which they called the Second Congregational Parish of Wells. It was located in Kennebunk Landing (on Summer Street). Daniel Little was invited to become the first minister, a role he held until 1801. In 1772, with a gift of land from Colonel Joseph Storer, the parish moved to its present location on Main Street across from the Brick Store Museum.

ABUSE OF TREATIES

Attacks on both Wabanaki villages and local European settlements caused a series of retaliatory actions on both sides. This behavior prevented the Wabanaki from maintaining neutral positions with respect to the French and English conflicts over the colonies. Treaties that were signed by the Wabanaki and European settlers in Maine in the 1700s were continually violated.

A series of violent actions against members of the Penobscot in Wiscasset eventually saw Massachusetts (of which Maine was a district) declare war on the entire Penobscot Nation in 1755. The colony declared the Penobscots to be enemies and traitors to the King. A man named Spencer Phips, acting Governor of Massachusetts at the time, issued the following proclamation (henceforth known as the Phips Proclamation):

Whereas the Tribe of Penobscot Indians have repeatedly in a perfidious manner acted contrary to the solemn submission unto his majesty long since made and frequently renewed[…] I do hereby promise that there shall be paid out of the province treasury the premiums or bounties following:

For every male Penobscot Indian above the age of 12 years, that shall be taken and brought to Boston, 50 Pounds. For every scalp of a male Penobscot Indian above the age aforesaid, brought in as evidence of theirbeing killed, 40 Pounds. For every female Penobscot Indian taken and brought in as aforesaid and for every male Indian prisoner under the age of 12 years taken and brought in as aforesaid, 25 pounds. For every scalp of such female Indian or male Indian under the age of 12 years that shall be killed and brought in as evidence of their being killed as aforesaid, 20 pounds. Issued the 3d day of November 1755. S. Phips…God save the King.

This was a bounty put on the people of the Wabanaki nations, specifically the Penobscot, by the colony of Massachusetts. Over the entirety of the 18th century, numerous treaties and understandings were agreed upon by the Wabanaki and European settlers, yet they were continually ignored. Even today, Congress has never ratified treaties between the Wabanaki and United States. You can learn more about these treaties through the Maine Memory Network (via Maine Historical Society).

Joseph Storer, a Lieutenant Colonel of the York County Regiment during the Revolutionary War, was said to be the wealthiest man in town at the time. He owned most of the property we now refer to as “downtown” Kennebunk, stretching from the Mousam River to where Hope Cemetery now stands. When Joseph and his wife Hannah became residents of the second parish (Kennebunk) in 1757, they built a four room, one-story house on what we now know as Storer Street. The following year, in 1758, he built the Storer Mansion. It was the first house in Kennebunk to be painted. The original 1757 house became a country store, and part of the Storer estate which ran from Main Street to the Mousam River and included an extensive orchard encompassing an enormous cider press. Joseph Storer also ran a saw mill and grist mill located on the eastern shore of Mousam River falls.

The first schoolhouse was also part of the estate, a simple structure built of logs that also worked as a sheep pin. In the 18th century children attended school in private homes or in structures that were little better than small barns. The first recognized schoolhouse in Kennebunk was the Mousam Schoolhouse, located at the corner of Sea Road and Summer Street, constructed in 1770. The oldest schoolhouse for which a photograph exists was the schoolhouse in the Parish Yard, located behind the First Parish Church that was constructed in 1797.

The Storers’ sons, Joseph and Clement, inherited the Storer property. Joseph and his wife Priscilla remained in Kennebunk and added to the original front portion of the Mansion in 1800. Joseph was a farmer, storekeeper and miller. He held two town positions, first as postmaster and then as collector of customs for Kennebunk, a position he held for sixteen years.

- School house in parish yard, c.1862

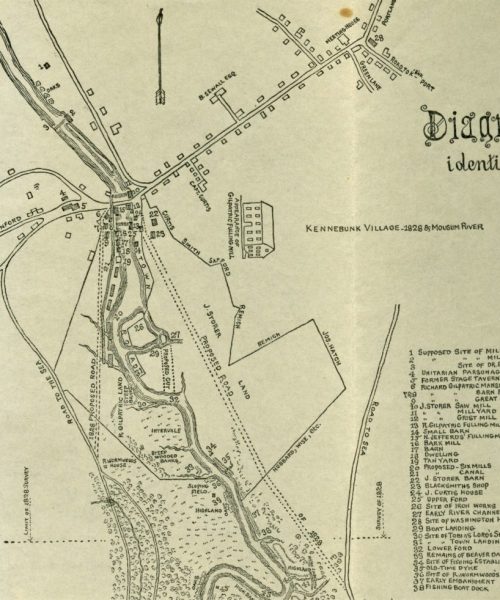

- Partial map of Mousam River by William Barry, 1909. Shows locations of mills and other historic sites.

In addition to the saw mills and grist mills being built during the 18th century, an iron foundry was established on the Mousam River around 1771 to supply tools to farmers and shipbuilders; and cookware to households. The foundry was built on a small peninsula of land coming out from the eastern shore of the Mousam just below the dams. The ore came from local bogs mostly gathered by farmers. Ore collection was a steady source of income from land typically considered “worthless.” After ten to twelve years of mining, the better-quality ore was exhausted. In 1785, heavy rains caused a great freshet that brought logs and debris down the river breaking through the dam and destroying the iron foundry, thus ending Kennebunk’s days of manufacturing its own iron.

Also in the 1770s, William Jefferds and Richard Gilpatrick built a fulling mill on the Mousam to provide homespun cloth. With the start of the Revolutionary War supplies of simple necessities such as iron or cloth from England and Europe were increasingly difficult to acquire. This lead to the need to manufacture more goods in Kennebunk.

REVOLUTIONARY WAR

The Tea Act of 1773 was one of several measures imposed on the colonists by the heavily indebted British government in the decade leading up to the American Revolutionary War (1775-83). In this tea tax, the British government granted the East India Company a monopoly on the import and sale of tea in the colonies. The colonists had never accepted the duty on tea, and the Tea Act rekindled their opposition to it. Their resistance culminated in the “Boston Tea Party” on December 16, 1773, during which colonists boarded East India Company ships and dumped their loads of tea overboard.

In March 1774, the townspeople of Wells (which included Kennebunk) resolved:

“That the late act of the British Parliament empowering the East India Company to export their teas to America subject to a duty is a daring infringement upon our invaluable rights and privileges…” They resolved that they would not receive any teas that had an unconstitutional duty on them either by the East India Company or any private merchant. Public sentiment in Kennebunk was so strong that many merchants hid the tea they had on hand.

Tensions had been rising for years between the colonies and British authorities, particularly in Massachusetts and its district of Maine, which had been the battleground (as had all of New England) for no less than seven out of (at least) 16 colonial wars fought in this century. After the Battle of Lexington and Concord occurred on April 19, 1775, a meeting of the town of Wells was called on the 24th to make preparations to send men to join the Revolution.

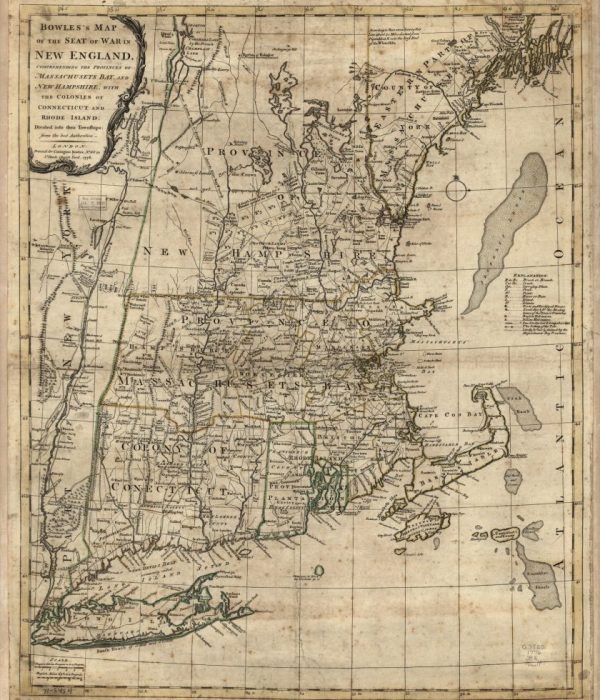

Bowles’s map of the seat of war in New England. Comprehending the provinces of Massachusets Bay, and New Hampshire; with the colonies of Connecticut and Rhode Island; divided into their townships; from the best authorities, 1776. Library of Congress

JOINING THE FIGHT

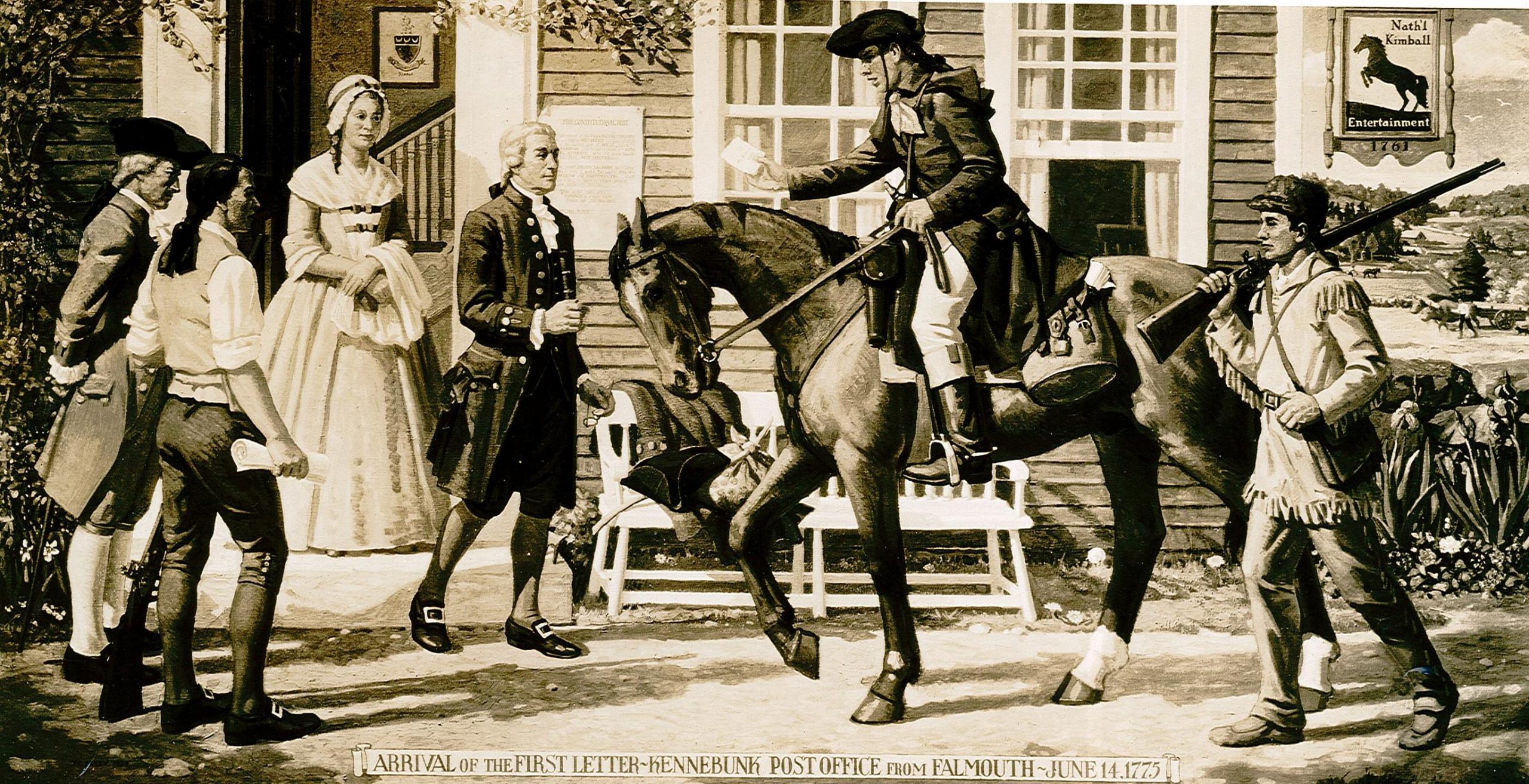

There were many Kennebunk men that went to fight, serving under the commands of Captain James Hubbard or Captain Samuel Sawyer. Tobias Lord was captain of a company stationed at Falmouth in 1776 and had five sons in the army at different periods of the war; one of them was wounded and died in Quebec. Those that were not off fighting were called upon to be watchmen, stationed from the mouth of the Mousam River to the mouth of the Kennebunk River. These men were there to give early notice of the enemies approach to the coastline.

“There was no able-bodied man in town who did not have something to do in the struggle for liberty. More than half of them in different periods of the war, were in service abroad.” E.E. Bourne

In the spring of 1776, a vote was taken and instruction was given to the Representative of the town, Joseph Storer: “We now inform you that if it should be necessary for the safety and happiness of said Colonies to be declared independent of Great Britain, that we are ready and willing to support such a measure with our lives and fortunes…”

Soon after this proclamation, news of the Declaration of Independence reached the town of Kennebunk and it was read from the pulpit of the Second Congregational Church the following Sunday to a packed crowd. There were a few local men that died during the war, including Captain James Hubbard, who was killed in Cambridge and Col. Joseph Storer himself, who died at Albany in October 1778.

The American Revolution was a long, hard-fought conflict from its beginnings in Massachusetts in 1775 to the official end of the war in September 1783 when the United States government and the British Parliament officially agreed to the Treaty of Paris. It recognized the colonies’ independence and drew lines between British Canada and the new country in North America.

Where did the Abenaki go?

Today, you will hear about the four federally-recognized tribes of the Wabanaki confederacy, consisting of Micmac, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot. The confederacy historically includes the Abenaki, specifically the Eastern Abenaki, on whose land Kennebunk and Wells now exist. The Abenaki still live here today – yet their tribal headquarters migrated northward at the end of the 18th century.

After the America Revolution, an estimated 1,000 Abenaki had survived war and disease (from a population of 12,000). Seeking refuge in a safer and more supportive area, the Abenaki cultural center moved to Vermont and Quebec, Canada. The Abenaki are officially recognized in those areas; however, the tribe applied for United States recognition in 1982, and is still waiting.

SLAVERY IN YORK COUNTY

At the turn of the 18th century, the work of enslaved peoples fueled the economy of the American colonies. While the majority of enslaved men and women lived in the southern colonies, slaves existed here in Maine. The majority of slaves – bought as property – in York County were purchased at a market in Wells which sold a variety of materials (its historical location is not currently known); or at a home called the “Weare house” in York (the home was later demolished).

Several Kennebunk and Wells families were known to own slaves in the mid/late 18th century. Much of this knowledge has been passed down through wills and estates, in which male relatives often bequeathed ownership of a black or indigenous person to their widow or children. More research continues in this area.

As historian Edward E. Bourne wrote in 1875:

Slaves were generally purchased in Wells. In the latter part of the slave era there were many small vessels owned on the seaboards, which were employed in the West Indies trade, by which they were readily transported here. Almost every vessel would return with a few and they were purchased at very low prices.

As historian Sally Merrill wrote in her journal article Cumberland and the Slavery Issue:

“By the mid eighteenth century, informal trade in slaves was replaced with a more formal system, as the demand escalated beyond the upper class to the upper middle class.”

She continued:

“Although black slaves were integrated into colonial life of their slave owners, they were kept apart and subordinate to white communities. At the time, in some towns, church attendance was mandated by law, but slaves were accommodated in special balconies or specific pews.” This is so in the case of Kennebunk and Wells. Evidence of a separate seating area for enslaved people (later freed people) on a balcony above the rest of the pews still exists in Kennebunk’s original meetinghouse, which is currently the Unitarian Universalist Church on Main Street.

Slavery existed for roughly 120 years in the region of Maine, before the state of Massachusetts (and thus its district of Maine) banned slavery in 1783. Local enslaved black people by the names of Sharper, Primus, Peg, Salem, Phillis, and “Old” Tom (who was the last of the settlement to pass away, in 1831), among others, were released from their forced service and took up residence along the edge of town.

The area of their settlement is known from maps of the time period. It is currently protected on state-owned land, and there is archaeological work being done to preserve the site and learn the history that is held there. Its current location is kept private in order to conserve the settlement’s remains until a full study can be conducted.

FROM THE BRICK STORE MUSEUM COLLECTION

This instrument was used to measure the altitude of the Sun or a star above the horizon to find one’s geographic position at sea.

Capt. Hugh McCulloch was born on 8 May 1773 in Arundel, Maine. He married Abial Perkins, daughter of Thomas Perkins Jr. and Susannah Hovey, on 10 April 1794 in Church of Christ in Arundel. They ran away to marry because both sets of parents thought they were too young. Capt. McCulloch was a trader and shipbuilder and soon became one of the richest man in Kennebunk. Between 1801 and 1822, he was known as the principal owner of at least 17 vessels.

For Colonists coming to America, firearms were essential tools and the powder horn served as its constant companion. The powder horn was introduced to America from Europe, where they were developed alongside gunpowder. Gunpowder had to be kept dry to be poured out easily; any dampness would make it form into cakes and prevent it from burning at all. Powder horn was often made from animal horns such as cow or ox which was easily and cheaply obtained. Animal horns were naturally waterproof, hollow inside and durable making them the ideal container. They were most common between the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, a fairly short period of time (1754-1783).

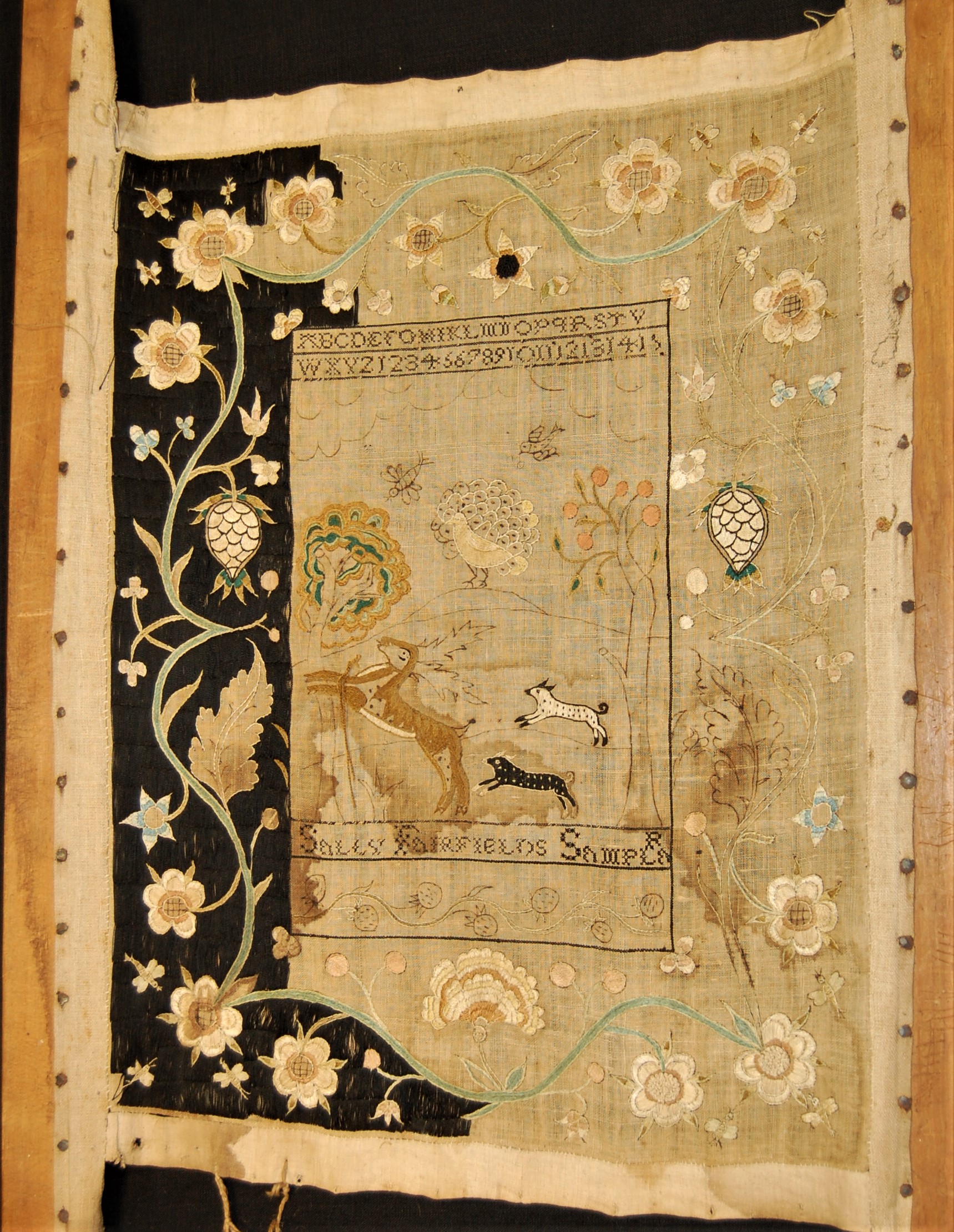

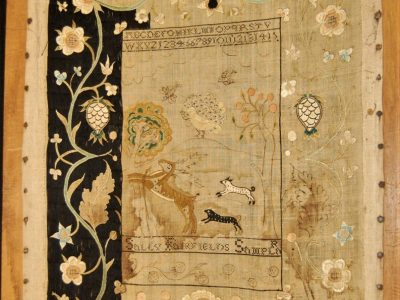

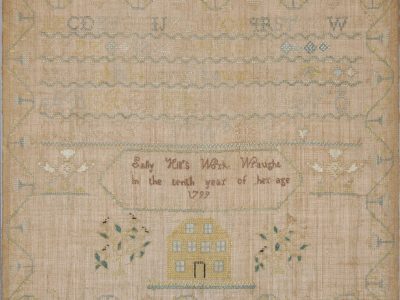

By the 1700s, samplers depicting the alphabet and numbers were being made by young women to learn the basic needlework skills needed to run the family household. Usually, a boy would be taught traditional academic subjects, while a girl might be tutored in just the basics of reading and arithmetic. Instead of academic studies, girls were usually sent to schools that taught an assortment of skills considered “female accomplishments”—music, watercolor painting, comportment, manners, and sewing.

As part of a young ladies preparation for the responsibility of sewing clothes and linens for her future family, most girls completed at least two samplers. The first, which might be undertaken when a girl was as young as five or six, was called a marking sampler. Marking samplers served a dual purpose: they taught a child basic embroidery techniques and the alphabet and numbers. The letters and numbers learned while embroidering a marking sampler were especially useful, since it was important that any homemaker keep track of her linens, some of her most valuable household goods. This was accomplished by marking them, usually in a cross stitch, with her initials and a number.