A Presidential Pardon

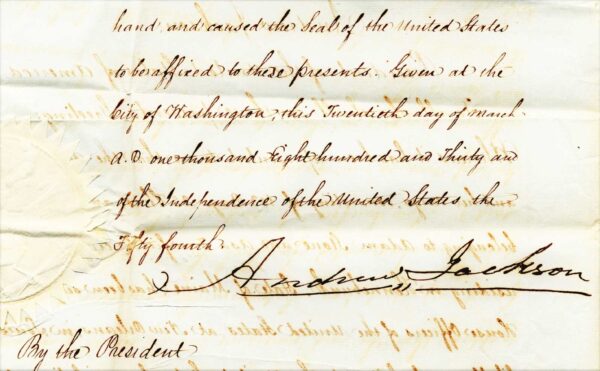

On March 20, 1830, the following statement came forth from the White House: “Whereas it has been represented to me that the American Brig Volant … belonging to Adam Stone and Asa Fairfield, citizens of the United States residing in Kennebunk, State of Maine, has been seized by the Customs House Officers of the United States, at New Orleans in Louisiana, and libeled as forfeited to the United States for a violation of the act of Congress prohibiting the importation of slaves … and whereas it has been made satisfactorily to appear that the said owners are entirely exempt from any suspicion of fraud, or participation whatever in the transaction touching upon the breach of the law above recited…. Now, therefore, I, Andrew Jackson, President of the United States of America … have remitted and do hereby remit the forfeiture aforesaid, and do hereby order and require that the … prosecution … against the said brig and her cargo … be forthwith stayed and dismissed.”

An interesting document to encounter, especially if one has been focused on researching such local history for Kennebunk and its neighboring towns, as I have been for a couple of years with a group that we named “Just History.” This document was shared with me by a wonderful local historian, Sharon Cummins, but she had not been able to locate any additional information on this event. For what act of “importation of slaves” had the owners of the Volant been pardoned? Had they been engaged in any similar transgressions? Could any contemporary accounts be found?

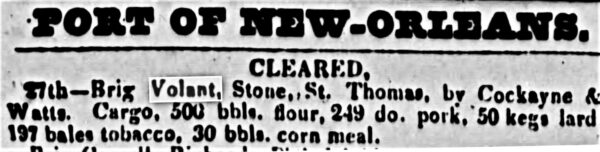

The Volant had been built in Cape Porpoise, a part of Kennebunkport, in 1821. A search of the shipping news in various newspapers revealed that during the 1820’s, the Volant regularly plied the waters between New England and a variety of southern ports, including Charleston and New Orleans, Port au Prince and Aux Cayes, Guadeloupe, and even as far as “Buenos Ayres” and Montevideo. Coffee was a mainstay of the cargoes transported, but other declared cargo included Moscovado sugar, “heavy Surinam molasses,” “logwood,” mackerel, flour, tobacco, lard, hams, pork, corn meal and feathers.

But what of this specific voyage and pardon? An extensive online search led to the Papers of Andrew Jackson at the University of Virginia Press, and there a mention of another Jacksonian pardon on that same date, a “remission of forfeiture of Adelaide Adam’s goods and slaves, seized for her unwitting violation of the ban on slave importations.” That enabled me to track down the pardon itself, which conveyed that Adelaide Adam, widow Vannel, was a resident of Puerto Rico and had arrived at New Orleans in December 1829 on board the Volant (“Fairfield, master”) with a negro female slave with two very young children. The pardon excused her “unwitting” act of importation of slaves, provided she paid all costs and gave “security that the Negro slaves be sent back to the island from whence they were brought.” It was signed by President Jackson and his Secretary of State Martin Van Buren.

Was this act truly “unwitting?” Was Adam’s intention to sell these three slaves in New Orleans rather than bring them back with her to Puerto Rico? I have not yet been able to find any contemporary accounts that might have shed any further light on this episode. I corresponded with Kate McMahon, who works at the Center for the Study of Global Slavery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. While she hadn’t encountered this tale, she noted that she’d “find it very difficult to believe that Adam—and the vessel owners—weren’t aware of the laws banning the importation of slaves into the United States. There was very little in the way of prosecutions of people breaking the laws of 1808, 1818 and 1820 during the 1820s and 30s, which allowed the foreign slave trade to flourish.” She continued “Polk also pardoned American slavers during the antebellum period, and a number of scholars have argued that the apathy of the US government to prosecute Americans involved in the slave trade — both transporting enslaved people to the US directly or to other countries — led to the rapid increase of Americans participating in the slave trade during the 1830s and 1840s.” She concluded that “while we likely cannot know exactly what Adam knew, we certainly know that as merchants and captains, Fairfield and Stone would have been well aware of the ban and that they were treading on dangerous ground. However, it is likely they also knew that there were few who actually suffered any real consequences throughout the history of the ban, from 1808 to 1862.”

The fact that Adam was not a U.S. resident no doubt makes it more difficult to track down any further accounts of her background or this episode. I did find that she purchased a slave in New Orleans in 1834, but I couldn’t access the actual record of the sale. If anyone has any further thoughts on this episode, or access to any Puerto Rican records of Adelaide Adam, widow Vannel, I’d be delighted to hear them.

One final note. On September 30, 1830, it was reported in the New Orleans Advertiser that “a fire burst out we know not how on board the brig Volant, lying opposite the city on the other side of the river. The conflagration was so violent that nothing has been saved but her chains and a few ropes….The fire must have been maliciously set, for no cookery was made on board the Volant.”