Indigenous Story of Southern Maine

New Research in Southern Maine

Studying the canoe

Canoe Excavation

- Stone tool found off of Cape Porpoise

- Projectile Point, 7000 B.P.

- Rhyolite scraper used for cleaning animal hides

- Collection of rhyolite flakes produced when a rock is struck with another rock, piece of antler, or bone in order to create a sharp edge on a stone tool

- Quartz Projectile Point, 4000 B.P.

- Projectile Point, 3,800-3,600 B.P.

- Ground Stone Fishing Net Weight. Found in Wells.

- Ground Stone Ax

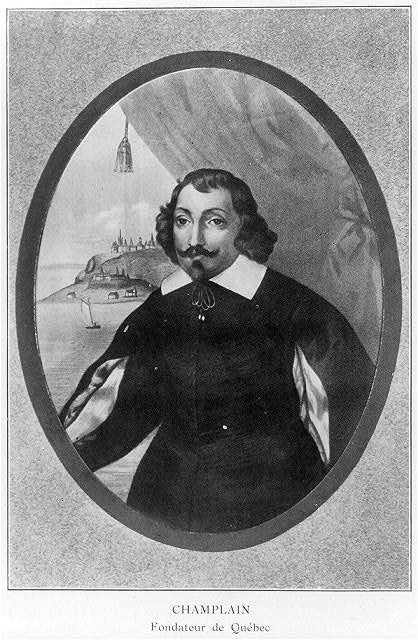

French Map of New England, 1685. The area highlighted in red depicts what they believed was a distinct indigenous culture, separate from other regional tribes.

Early Descriptions

First Encounters

Today

Through these challenges, indigenous peoples are still here. Whether they belong to federally-recognized Wabanaki tribes or are descended from the Abenaki or Almouchiquois peoples who are not federally-recognized today, they have persisted. Many of their early traditions have survived and continue to flourish in communities throughout Maine.

In the 20th Century, the Wabanaki were some of the first artists to cater to the growing tourist trade in Kennebunk. In numbered tents along River Road (now Ocean Avenue), Wabanaki artisans placed advertisements in local newspapers for baskets, canoes, and other traditional craft; and even instructed tourists in canoe paddling, sitting, standing and walking. Joseph Ranco, Penobscot, was probably the first to build canoes in Kennebunkport, beginning around 1890, bringing his supplies by train from Old Town. Indigenous artistry continues to thrive and grow in the 21st Century.

Today, the four Maine-recognized tribes are the Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Penobscot and Passamaquoddy, known collectively as the Wabanaki, “People of the Dawnland.” Although most of Maine’s Native peoples belong to one of these four federally recognized groups, other Native people live in towns and cities across our State and contribute greatly to our diverse culture and memory.

The Wabanaki have many stories that preserve the history of people in the Dawnland. Please invest time in learning the history and culture of the Wabanaki people through a variety of resources offered around the State, beginning with the Maine Wabanaki REACH organization and Maine’s tribal museums. Institutions across the state, including the Brick Store Museum, are working to indigenize our shared human story in 2020 and beyond. In the celebration of our shared history, we also must look to the future to protect our diverse cultures from disappearing.

Research Continues

Unfortunately, some of the history relating to specific tribes in southern Maine is buried. Scholars have referred to this area’s history as a “no man’s land” because of early disruption by European settlers that unseated tribes in this area, so that much of the established culture was not observed before tribes either merged with other northern groups or, in the case of the Abenaki, moved their cultural centers to Vermont and Canada. Additionally, little archaeological research has been conducted in Southern Maine. However, descendants of these tribes are still in our community today, and we thank them especially for helping to keep this culture alive. The Museum pledges to continue its work of highlighting and investing in this important local history and culture, and welcome your help to do so.

Learn more about this work by visiting our Archaeology page.