Welcome to the Century Saturday Series!

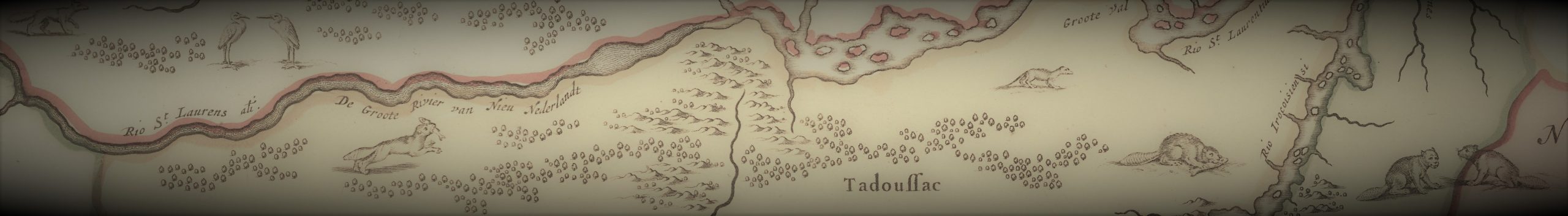

It’s time to explore 18th century Maine.

This program was originally created as a live museum event, included in the price of daily admission. While this online program is free, please consider making a donation in lieu of the cost of a ticket (only $5!), or any amount, to support the Museum’s educational programming.

Welcome message from Cynthia Walker, Director

Pop-Up 18th Century Kennebunk Exhibit:

Guest Lecture: Theodore Lyman’s New England Experience

Michael Maler, Regional Site Manager for Metro Boston at Historic New England, discusses the life of Theodore Lyman, who began his life humbly in the 18th century.

Lyman’s story weaves between Kennebunk, Boston and Waltham, among other places, during the late 18th century.

Focus: Music in the 18th Century

Music in North America, in what is now the United States, began as traditional indigenous tribes’ spiritual music. This music continues today as it is handed down through tribal members.

Click the button below to hear an example of traditional Maine Passamaquoddy music, as performed by Wayne Newell and Blanch Sockabasin at the Library of Congress.

As colonists and explorers arrived, European music – often religious – came as well. In 1619, the beginning of the slave trade in the colonies saw African people bring musical traditions with them in the form of traditional banjo music.

African enslaved people were brought to the colonies and introduced the music world to instruments like the xylophone, drums and banjo. The diverse music of the United States comes from the diverse peoples who both lived here and arrived here in the 18th century. As you listen to the various clips in this segment, you might hear how current “American music” was inspired by the music of the 18th century, including country music, folk music, and popular music.

Colonial music in the 18th century included ballads, dance music, folk songs and parodies, and musical comedies and operas. Violins were by far the most popular instruments of the era. People of various different classes at the time, from wealthy landowners to servants to enslaved people, played violins or fiddles.

Although New England is famous for its Puritan beginnings, dancing was popular in this area by the 18th century. There were still some Boston ministers who wrote against the practice (i.e. Increase Mather), but as the settler population grew, dancing became a mainstay.

Below, you can find a recording of a banjo song played by former enslaved man John Scruggs in 1928.

George Handel, Joseph Haydn, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart were creating music at this time in Europe, too, though it likely did not arrive in the colonies until a few years after it was heard in Europe.

The First New England School is considered one of the first uniquely colonial American invention of music. The most unique feature was that the voices, male and female respectively, doubled their parts in any octave in order to fill out the harmony. This generated a texture of chords that was unknown in European tradition.

Included in the First New England School were William Billings, a native of Boston, who was a tanner by trade. He taught himself music. Billings has been called the “first American composer to emphasize strongly a creative independence and to flaunt his personal idiosyncrasies” in his music.

Another member of the creative group was Supply Belcher, who was born in Stoughton, Massachusetts, and then moved to Farmington, Maine. He published a songbook titled “The Harmony of Maine” in 1794, which included anthems, psalms, and fugues.

Musical theater in the colonies was also very popular as an entertainment. Most were performed with familiar folk tunes, with words strung together to create a comic story.

The most famous of these was The Beggar’s Opera, written in 1728 in London, as a reaction to the elite classes in London. It came to the colonies shortly afterward, and was performed here as early as 1750. So many colonists had scene or heard the opera that its songs – much like today – were sung at home.

You can read the entire script of The Beggar’s Opera via Project Gutenberg, HERE.

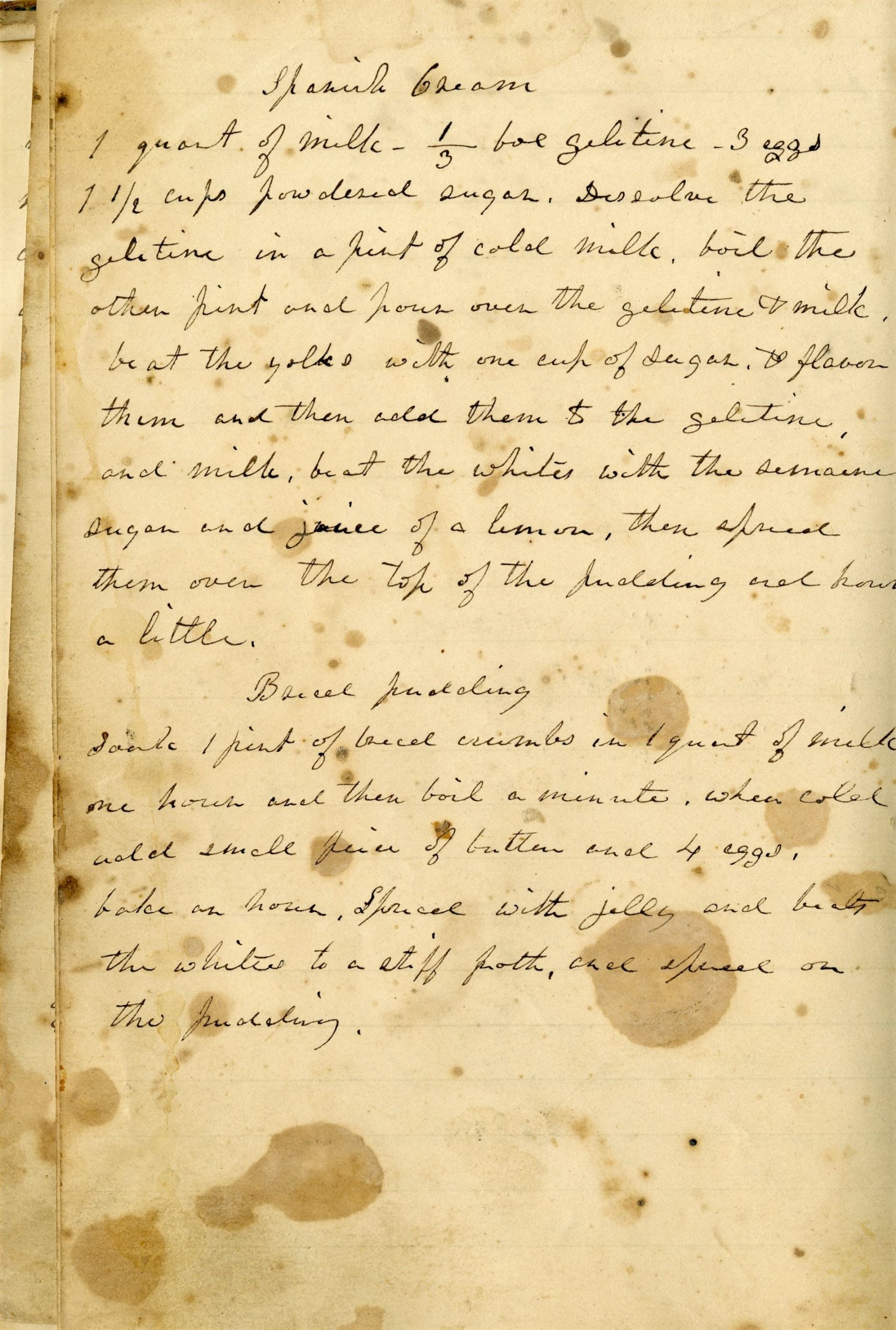

Activities:

Further Resources to Explore:

- Atlantic Black Box Project – studying the Atlantic Slave trade in New England.

- Native-Land – interactive map that helps us discover the indigenous land on which we all live, and what peoples lived here before the arrival of European settlers.

- Wabanaki Traditional Lifeways Study – completed by the Environmental Protection Agency. Further reading and detail on lifeways and traditions that continue today.

Questions?

Email the Museum at info@brickstoremuseum.org. We’ll post answers here!

More to See at the Museum: