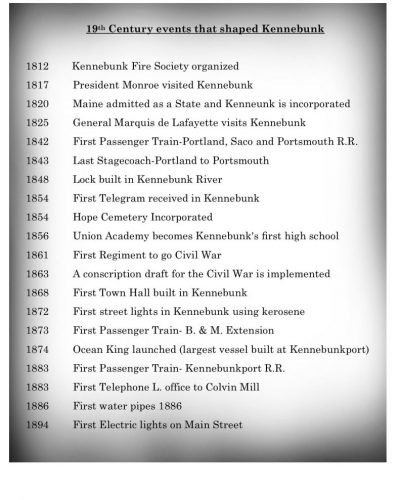

Kennebunk in the 1800s An Era of Change

The 19th century was a time of rapid growth, industrialization, and innovation throughout the United States. Profound development in transportation and technology sped up with the introduction of steam power and electricity. Inventions like the telegraph, typewriter, camera, and the telephone led to faster and wider means of communication.

The era was characterized by major economic growth, the abolition of slavery, development of large-scale agriculture, and the expansion of the federal government after the Civil War. With these changes came social upheaval and discourse on immigration, federal Indian policies, increasing demands for rights by workers, and equality for women and minorities.

Kennebunk residents born in the 1840s and 1850s experienced enormous changes in their lifetimes. For example, the major source of light would change from candles, to kerosene lamps, and then to electric light bulbs. They witnessed transportation evolve from horsepower to steam-powered locomotives, to electric trolley cars, to automobiles.

Over those decades, the town became more diverse to include immigrants and rural migrants moving to the area to work in the local mills. Kennebunk transformed from a largely rural agricultural society to a town with a rising middle class and the foundation of many of the modern amenities we still enjoy today.

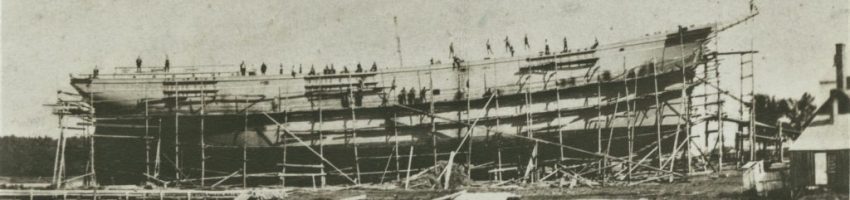

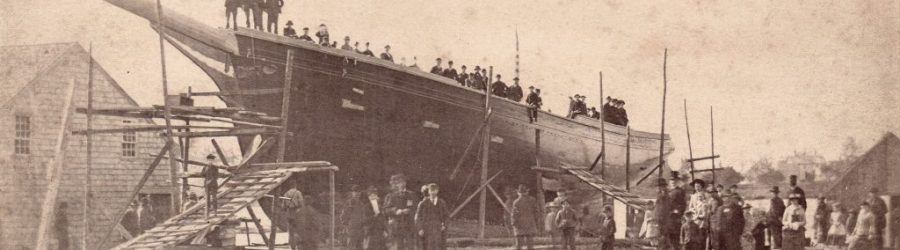

SHIPBUILDING IN THE KENNEBUNKS

The Port and District of Kennebunk customs district was established in 1800 in recognition of increased maritime activity in the Kennebunks and the growing shipbuilding industry. Local builders and shipmasters no longer had to travel to Saco to register their vessels. The new customs house was in Kennebunk until 1815 when it was moved to Arundel (Kennebunkport), which was the actual port of the district.

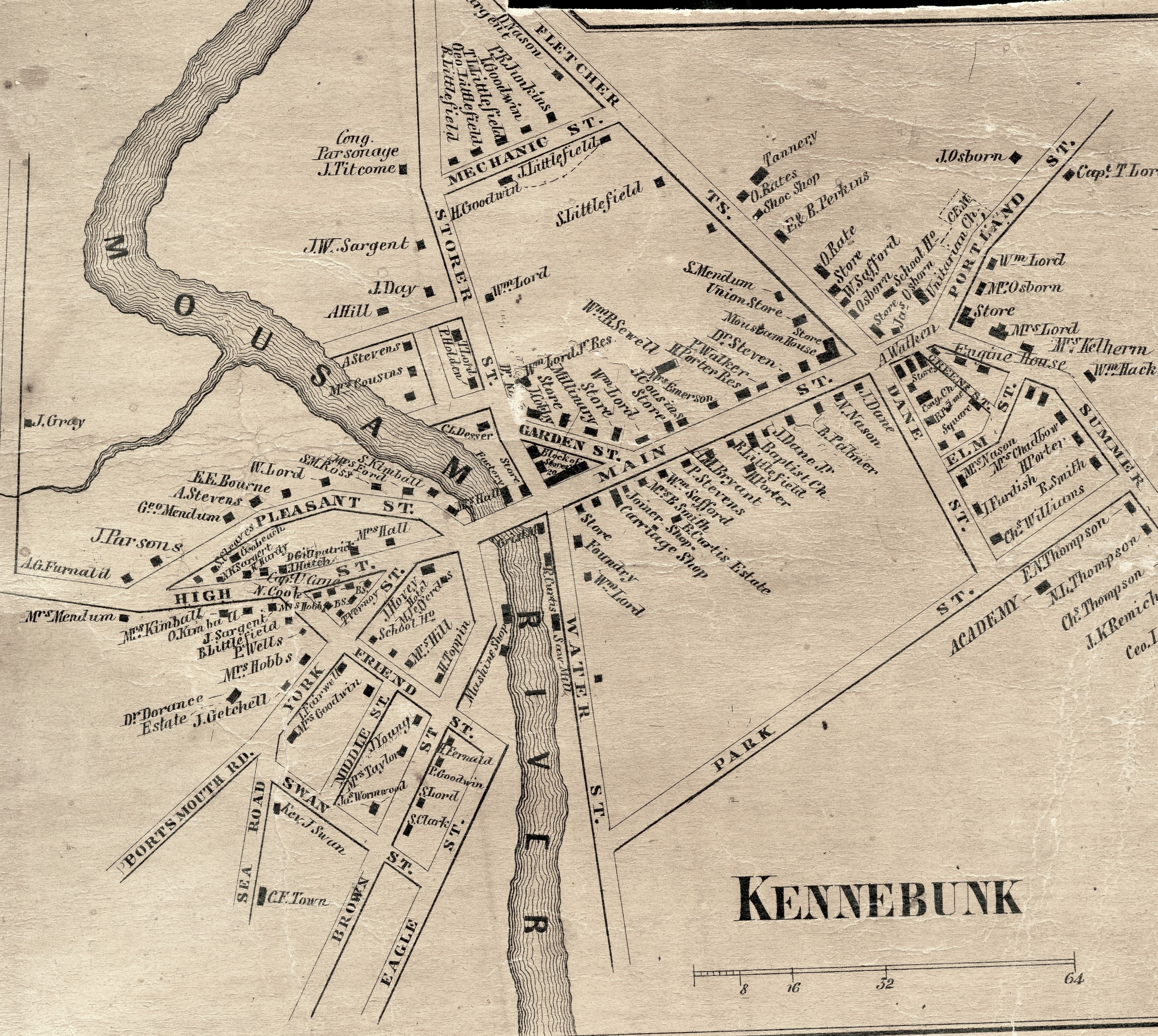

By 1800, there were six major shipyards located at Kennebunk Landing; those sites produced almost 400 ships by 1830. These locally owned ships were able to navigate the tidal rivers to load cargo and were equally adept at maneuvering through the coral reefs of the Caribbean, one of their primary destinations of trade.

The economic influence of this burgeoning shipbuilding industry spread far beyond the shipyards. This booming industry affected the prosperity and development of the entire region. Building materials came from local wood and sawmills. Cargoes were loaded with local products such as lumber, ice, hay, fish and potatoes to points south and east. Bakers, shopkeepers, coopers, blacksmiths and farmers provisioned vessels for their voyages while crews and laborers were made up of local men and boys.

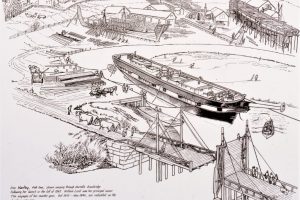

Ships sailed to ports in the Caribbean, Asia, Europe, and the American South and Northwest. The most common goods loaded at southern and Caribbean ports for European markets were cotton, flour, tobacco and sugar. Stronger and larger vessels were continually needed to support this growing trade; by the 1850s, the shipyards were launching three-masted, 800-1500 ton sailing ships into the river. Soon they were far too large to navigate down the Kennebunk River so the shipyards moved to Lower Village and Kennebunkport. Between 1854 and 1918, three to four hundred more wooden sailing vessels were built in these shipyards. With the wealth made in building ships and from the cargoes they carried, maritime businessmen of the Kennebunks built houses and public buildings along roads that led to their shipyards and wharves, creating the village centers that still exist today.

- Ship Hartley above Durrell's drawbridge, 1845

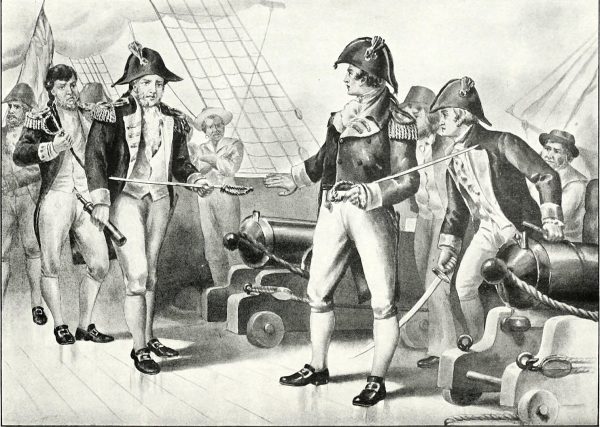

The War of 1812

At the start of the 19th century, Europe was embroiled in the Napoleonic Wars. France and Britain were locked in constant conflict. The United States traded with both countries, which was not acceptable to either country. Each one started to harass American merchant vessels, Britain in particular, to the point of kidnapping sailors off U.S. ships and drafting them into the Royal Navy. In 1807, the States were united in their anger against the British yet again. In response, President Thomas Jefferson instituted a controversial embargo, blocking U.S. ships from doing any business with foreign lands. This embargo hurt the coastal communities of New England the most and had a disastrous effect on the early shipbuilders of Kennebunk. Congress declared war on June 18, 1812, which did not have strong support in New England due to further disrupted trade routes.

The War of 1812 had two lasting effects on Maine. The first was political, the Federalist Party, which had been dominant in New England, fell from popularity and the Democratic-Republican Party that supported separation from Massachusetts and statehood for Maine rose to prominence. One of the arguments used to gain statehood was the fact that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts was incapable of protecting Maine during the latter months of the war. The second effect was that the war motivated many Mainers to look inland for their livelihood. Cut off from the sea, they began to further develop river-powered mills and factories leading to the industrial age.

Women's Industry

Elizabeth Perkins Wildes Bourne (1765-1844) of Kennebunk ran a successful cottage industry to support her large family during the economic failure of the war.

Eliza’s first marriage was to a local sea captain, Israel Wildes, with whom she had three daughters with before he tragically died of illness in 1793 on a voyage to England. Two years later, she married widower John Bourne, a Kennebunk shipbuilder, who had six children from two previous wives. By 1810, John and Eliza had several children of their own together, for a very large family of 15 children.

Although taking care of 15 children is impressive enough, Eliza Bourne began at an early age a cottage industry of designing and fashioning bonnets, cloaks and gowns. Soon after she married John Bourne, Thomas Jefferson imposed the Embargo Act of 1807. Eliza supported her large family during this period of hardship by expanding her business to the manufacture of white cotton coverlets.

Her three teenage daughters and several younger children provided a ready labor force to help. Her coverlets soon had a reputation for quality throughout New England. In 1809, her daughter Abigail thought to send a coverlet as a present to President James Madison and First Lady Dolley Madison. The First Lady was so impressed with the coverlet that she acknowledged the gift with a thoughtful letter and a pair of gold earrings and a chain. Unfortunately, the coverlet is believed to have been lost in the White House fire of 1814. Dolley Madison’s thoughtful reply to the gift remains as a testament to quality of the coverlet.

She wrote:

I have just now had the pleasure to receive the valuable and beautiful counterpain from Miss Wildes which does much credit to her ingenuity and industry. I beg she will accept my sincere thanks for the singular favor as it is greatly augmented by her expressions of kindness for an unknown friend who can never forget her. I hope she will add to my obligation by accepting form me in return some token of my regard.

Eliza Wildes Bourne and her husband John Bourne sat for their portraits by the itinerant artist John Brewster, Jr. around the time of their marriage in 1796. Their portraits remained in their Kennebunk Landing home until 1979 when they were sold at auction. A new owner of Eliza’s portrait, which showed her in a high lace collar, dark dress and shawl, sent it to be cleaned. The conservator discovered extensive over-painting. When it was removed, the original portrait was revealed. The Brick Store Museum purchased the portrait in 1996 – you can see its image at left.

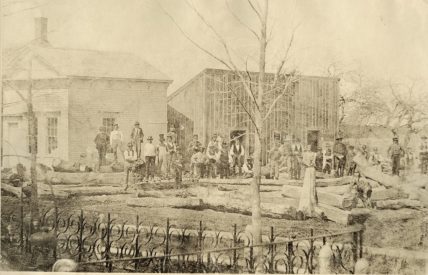

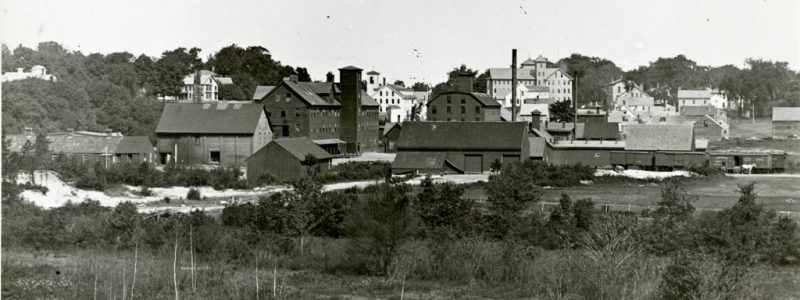

The Industrial Revolution

While shipbuilding dominated the Kennebunk River in the 19th century, another transformation was taking place on the Mousam River, it was becoming the center for manufacturing with companies producing cotton, twine, shoes and an innovative product called leatherboard. The Industrial Revolution was completely changing how people in Kennebunk worked and lived, moving from a largely agricultural society to one centered on manufacturing.

In 1826, Kennebunk Manufacturing Company was incorporated and purchased the property along the Mousam River including the upper and lower dams, the land on the east side of the river and on both sides of Brown Street. The company reconstructed the dam in the center of town and soon began to construct a new cotton factory on that site. Unfortunately, the company was not well managed and toward the end of 1828, all the property was sold at auction. It wasn’t until 1834, that a new company was firmly established in its stead called the Mousam Manufacturing Company which was for the purpose of manufacturing iron, steel and woolen and cotton goods.

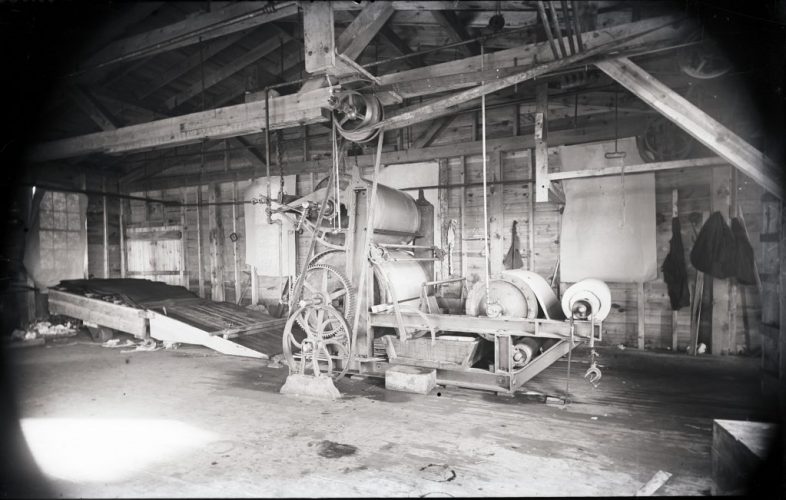

The 1850s and 1860s marked the true beginning of modern manufacturing in Kennebunk. In 1851, the Warp Mill was built to spin cotton yarn but it only lasted a few years. It was remodeled in 1865 and leased by Solomon Hewitt, for manufacturing yarns, twines, carpet warps and wicking. In 1852, John Ferguson started his sash and blind factory in the old Pierson tannery buildings.

New mills continued to be built in Kennebunk in the 1870s. Davis Shoe Company formed in 1877 and built a factory on Main Street and Storer Street which is the site of the Lafayette Center today. The largest factory began in 1876, the Leatherboard Company constructed the first of many buildings on Water Street for the manufacture of leatherboard products. Leatherboard was made from scraps of vegetable-tanned leather that were ground and pressed into sheets that was then used to produce everything from steamer trunks, insulation for electrical equipment, wastebaskets, shoe counters, and more. For nearly a hundred years, mills and factories were a presence on the Mousam River, providing jobs and dominating the landscape of Kennebunk.

The Missouri Compromise

The divide over slavery that led the country to Civil War is inextricably linked to Maine’s admission into the Union. In 1818, Missouri sought to enter the Union as a slave state. This would “tip the scales” of representation for free and slave states, as there would be twelve slave states to eleven free states. To make it equal, Congress came up with the Missouri Compromise in 1819. It included the admission of Missouri as a slave state and the admission of Maine as a free state.

On July 31, 1820, the Kennebunk district of the Town of Wells officially separated to become the Town of Kennebunk. On August 14th, 1820, Kennebunk’s first town meeting was held in the meetinghouse of the First Congregational Parish. The population of Kennebunk was 2,145 people, and the town’s valuation was $235,023.40.

There were many people in Maine that didn’t want statehood through the Missouri Compromise, the abolitionist movement had grown throughout the State. Although the North’s economy no longer needed slave labor, northern shipping, fishing, farming, and finance profited from the South’s slave society. Kennebunk shipbuilding and shipping industry also played a role, cotton was the cargo of choice and profit, and many Kennebunk Landing vessels were built specifically to carry cotton. The Golden Eagle built in Kennebunk Landing had a capacity of over 5000 bales. Though the compromise initially helped soothe some tensions, it also enshrined the very things that would later tear the nation apart. In 1861, the Civil War began.

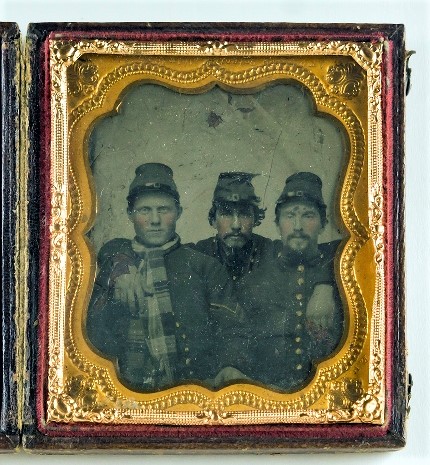

The Civil War

Many Kennebunk citizens celebrated after Lincoln won the election. “A great change has apparently taken place in the minds of many Republicans, at least in this vicinity,” Andrew Walker wrote. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Kennebunk had just over 2,000 inhabitants.

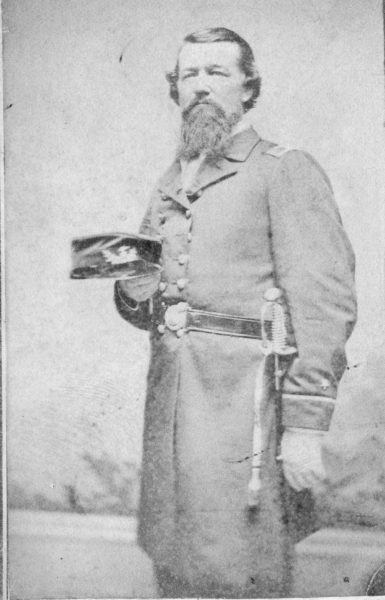

Like today, opposing views on the war were consistent topics of conversation in Kennebunk. While most people in town agreed with the Abolitionist platform, many men in town spoke out against Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and supported each state’s right to choose the legality of slavery or not. When the time came, Kennebunk men and boys joined the fight. According to the Maine Historical Society, “Maine met its draft quotas easily in the early months of the war, furnishing altogether 31 regiments of infantry, three of cavalry, and one of heavy artillery, along with assorted companies of artillery, sharpshooters, and unassigned infantry, and 6,000 sailors for the Navy. Approximately 73,000 Mainers served in the Union Army and Navy during the war, the highest figure in proportion to population of any northern state.”

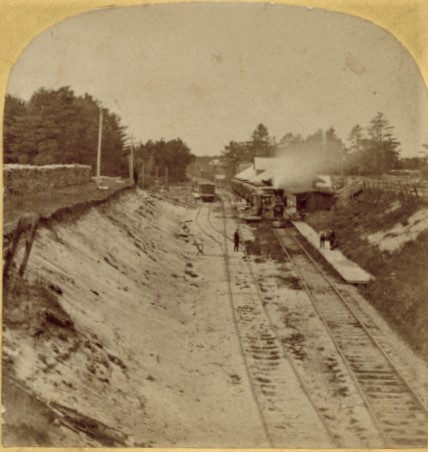

Because of Kennebunk’s position along the rail route from Portland to Boston, each of the Maine regiments (each time numbering about 900 men) traveling to Washington passed through or stopped at the Kennebunk rail depot in West Kennebunk. Many townspeople often gathered at the Depot to wave at and talk to the departing soldiers. The daily news of marching troops, skirmishes, and deaths became the norm. Andrew Walker noted how quiet the streets of the town had become, as so many men had left to fight.

The economy in Kennebunk suffered as the war continued. With so much of the population at war, Andrew Walker believed that people in Kennebunk would not be able to do “business enough during the coming winter to pay their way.” Local companies and ship owners noticed the change, too. Factories on the Mousam River had too much product on hand that did not sell. Captain Nathaniel Lord Thompson noted that when the Civil War began, there were about fifty vessels that went on foreign voyages from Kennebunk. By 1864, no more than ten vessels were owned in both Kennebunk and Kennebunkport.

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate troops to the Unions marking the beginning of the end of the long four-year war. One day after General Lee’s surrender, Kennebunk received a telegram at 8:00am announcing the important news. Immediately, the news spread, the church bells were rung throughout town, children were let out of school and all the U.S. flags in the village were raised high.

Discrimination

Reforms were introduced in some areas of society during the 19th century while injustices persisted in others. After the Civil War, discrimation affected a range of people who had recently immigrated into the country, from Mexican immigrants to Irish Catholics. Chinese immigrants working on railroads were at risk of violence against them. Native American children were sent to special schools where they were removed from the influences of the tribe and were taught how to become more assimilated into mainstream American culture.

Although slavery had ended, violence against black people in the United States was significant during the Reconstruction period, as were racial stereotypes. Racial segregation laws meant that opportunities and physical spaces were separate for whites and black people in certain states. In addition, local customs and government policies also encouraged inequalities at every level of society.

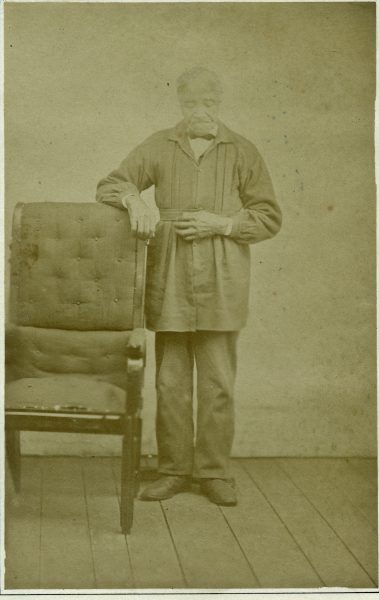

This is an image of freed slave, Lancaster Hodges, the image was passed down through Edith Barry’s family, a descendent of the Cleaves family and founder of the Museum. This is the only image in the Museum’s collection of a known freed slave.

Lancaster Hodges, was born a slave in Danvers, Massachusetts on January 31, 1771 to Lancaster and Ellis Hodges. His parents and family were owned by Daniel Jacobs, who ran a chocolate factory in Danvers. Mr. Jacobs had a large family and when he closed his business, he distributed his servants among his children. His youngest daughter, Abigail, married Captain Putnam Cleaves and Lancaster Hodges was given to them. Daniel Cleaves, only son of Putnam, moved to Saco around 1792 and Lancaster came with him. In 1797 Lancaster moved to Brownfield and lived with Daniel Jacobs Jr., first son of Daniel Jacobs the original slaveowner, and lived there until he died in 1878 at the ripe old age of 107 years old.

Tourism comes to Kennebunk Beach

Kennebunk Beach remained largely undeveloped until the mid to late 19th century, consisting of just a few scattered farmhouses connected by dirt roads. After the Civil War, summer vacations and leisure time became more achievable especially for the rising middle class. Train travel became affordable and easy. With increased industrialization and urbanization, people sought to escape the city and retreat to a more serene and rural setting.

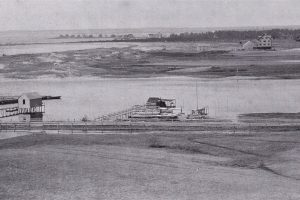

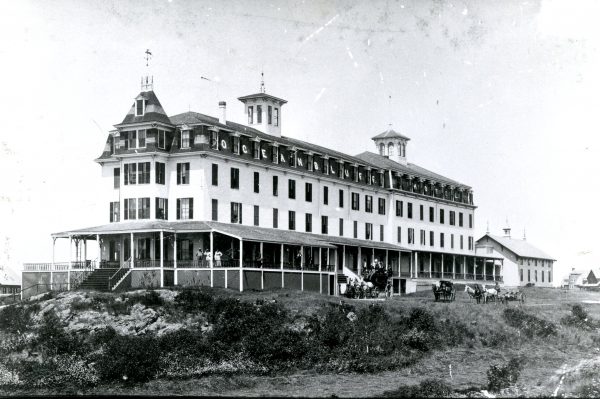

In Kennebunk, Isaac Gooch and later Owen Wentworth, were the first residents to take in borders at their Kennebunk Beach farmhouses beginning in the 1860s. However, it wasn’t until 1870 when a group of men from Massachusetts and several from Kennebunkport formed the Boston and Kennebunkport Sea Shore Company that the area became firmly established as a first class summer resort. The Sea Shore Company purchased over 700 acres from local farmers in order to sell them as cottage lots. And, in 1873, the Sea Shore Company built the Ocean Bluff Hotel at Cape Arundel.

This new tourist industry prompted the construction of cottages and grand hotels at Kennebunk Beach and Kennebunkport. By 1900, almost forty hotels were built along this stretch of coastline including the Nonantum, the Eagle Rock Hotel, the Atlantis and the Narraganset. Stage coaches from the Ocean Bluff and the other hotels, met every incoming train.

The Boston and Maine Railroad provided local residents and visitors at the turn-of-the-century easy access to and from the Kennebunks, Boston and New York. In 1872 the Boston & Maine, opened a branch line from South Berwick to Portland with a new station in Kennebunk providing a direct trip, seven times a day, from Boston, in only about three hours. The Kennebunkport Branch was opened in 1883, with four new stations that ran along the beach terminating at the new Kennebunkport Depot at the edge of the Kennebunk River. The new Kennebunk Beach Station was located near Sea Road and provided an easy walk to the nearby cottages, boarding houses and hotels.

The close of the 19th century saw a far different society then when it began. The factories and mills that lined the Mousam river were beginning to close. Shipbuilding on the Kennebunk River was also on the decline. Disparity between classes grew, fewer hours of work for a middle-class population meant more leisure time while others found themselves working in very poor conditions and enduring long hours.

For those in the position of having more leisure time, travel opportunities increased as did new forms of entertainment. Sporting events became increasingly popular, with baseball growing into its own as the country’s national pastime. Vaudeville emerged as a popular form of entertainment, mixing many types of theater, dance, and song into a variety show. Even movies were entering the scene, with the first publicly available commercial films released just a few years before the turn of the 20th century.

The Brick Store Museum Newsstand

Come Read All About It!!

Below are a selection of newspapers from the Museum’s archives.

Click on the link to read the news.

Weekly Visitor November 16 1811