This physical exhibition premiered at the Brick Store Museum in April 2014. It was updated to an online format in April 2020.

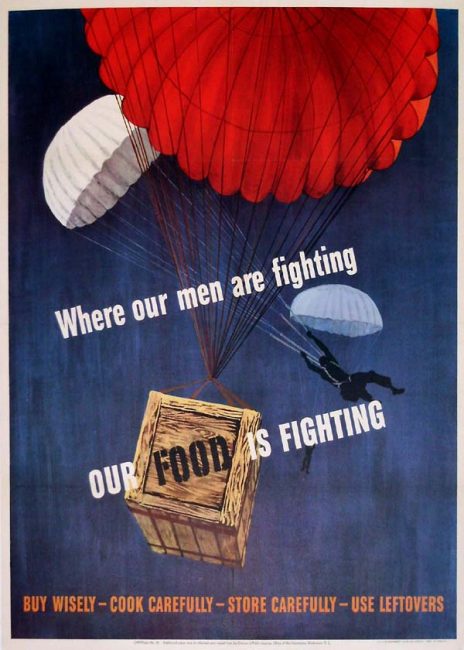

Our Food Is Fighting!

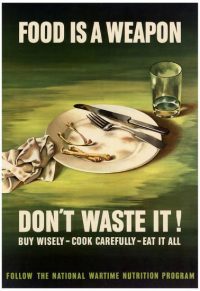

Food is universal. It is something that every person needs and understands. Situations that make it plentiful or scarce often instigate major events in history. During World War II, food was considered a weapon. It could be used to feed soldiers and families to strengthen our resolve; and it could be withheld from enemy forces to weaken their abilities. The material artifacts that fill this gallery tell the story of how food helped fight the Second World War, especially in the forms of rationing and Victory Gardens.

Families on the American home front during the 1940s were active participants in the war. Food, fuel, and other materials supported the 17.8 million American troops that served in all branches of the military from 1941 through 1945 – which meant those on the home front stretched, substituted, rationed, and made do with less. Not only were materials used in the war effort, but American production of these products plummeted due to labor shortages as the result of millions of men leaving the workforce to join the war.

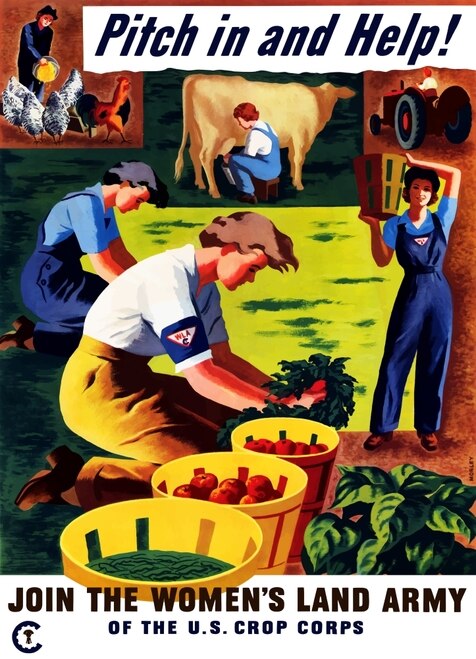

Raising an armed force and feeding themselves and their allies signaled a fundamental change in American society of the 1930s. With the vast war production effort, unemployment virtually disappeared. The need for labor opened up new opportunities for women and minorities. Economic output skyrocketed. The home front war effort required sacrifice and cooperation to be successful. That meant all Americans conserved resources, volunteered for civilian defense, and rationed food and other important war materials.

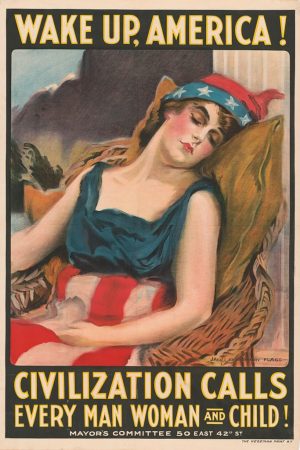

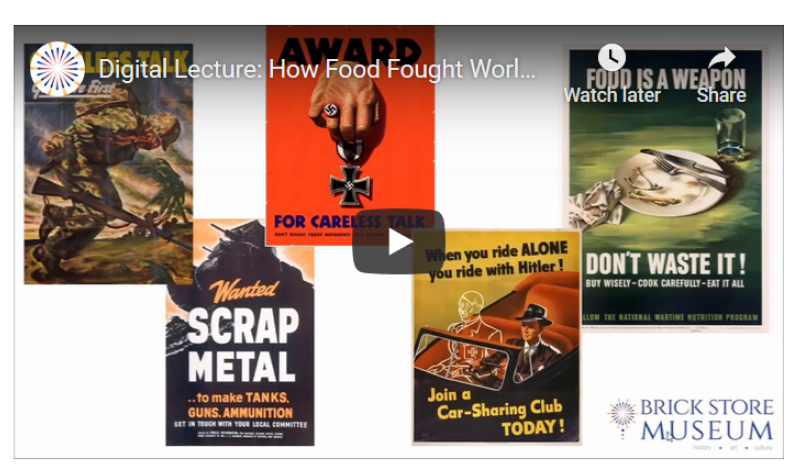

The American government focused its efforts on making families at home feel as though their sacrifices were just as important to winning the war as those made by the men on the front lines. Every scrap was saved; every meal planned out; nothing was wasted. Emotionally-charged propaganda posters and government leaflets were the chief ingredient in spreading the word.

Going to War

Nearly 40% of U.S. servicemen and women volunteered for military service during the war. 60% were drafted. The average base pay for an enlisted man was $71.33 per month, with officers receiving an average of $203.50 per month. After the United States joined the fight against Germany and Japan in 1941, nearly the whole world was at war. Europe had been embroiled in the fight since 1939.

Nearly 80,000 Mainers served in World War II, more than in any previous war. Over 2,150 Maine soldiers died in service to their country – including 206 men from York County alone.

Mobilizing a Nation

In the early 20th Century, the Committee on Public Information realized an important hurdle to advertising in America: the printed word was often not read, newsreels could be ignored.

How could the U.S. spread information? The billboard was something that caught even the most indifferent eye.

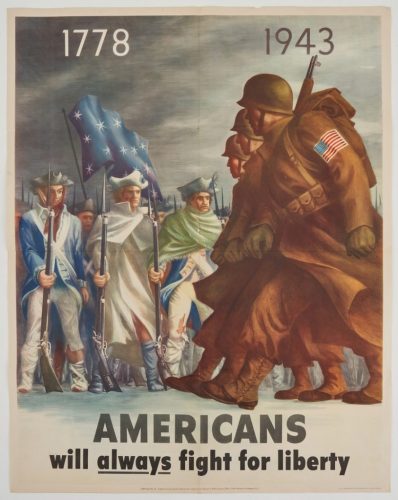

Propaganda posters, especially, were created during World War I and World War II to target and rally reluctant citizens to embrace the sacrifices demanded of them during those years. In an era before the internet, widespread radio, and television, these brightly colored, highly-visual posters were critical to spreading the word.

The Committee on Public Information wasted no time. In 1941, government officials incorporated the poster medium into their plans to convert the American economy to all-out war production. They realized that they needed the best artists in the country to create these posters to win over the American public. Artists, illustrators, and media specialists flocked to the government’s war effort. The main goal of the program was to transform every person from being an observer to being an active participant – voluntary cooperation rather than propaganda and coercion. Owning a share in America meant a lot more than monetary investment. American citizens had just been revived from the Great Depression, and before that, World War I. These posters mobilized a nation to action.

Posters were inexpensive to create, and ever-present. They hung everywhere. Thousands were issued by government agencies, businesses, and private organizations; all working to link the military front to the home front. Not all citizens were on board with the sacrifices required; posters and messaging were often the emotional charge that inspired shifts in judgement. Imagery was direct and sometimes frightening. Posters addressed every U.S. citizen as a combatant: the home, the farm, and the factory were arenas of war.

The Office of War Information wanted to

“See posters on fences, on the walls of buildings, on village greens, on boards in front of city hall and the Post Office, in hotel lobbies, in the windows of vacant stores – not limited to the present neat conventional frames which make them look like advertising, but shouting at people from unexpected places with all the urgency which this war demands.”

The Office of War Information (OWI) began in 1942 by Executive Order of President Roosevelt. It became the official clearing house for all posters, and contracted with commercial illustrators to design these posters, with which commercial illustrators contracted for their design. These illustrators were not paid for their artwork.

There were at least four government agencies that dealt with posters at the time: The Office of Facts & Figures; the National Advisory Council on Government Posters; the Office of Emergency Management; and the Office of War Information. To control the form of war messages, the OWI reviewed and approved every government poster from 1942 through 1945.

The OWI formed six basic propaganda themes for its poster needs.

1) The Nature of the Enemy

2) The Nature of our Allies

3) The Need to Work

4) The Need to Fight

5) The Need to Sacrifice

6) The American Spirit

Examples

The following examples show the variety of messages the OWI wanted to issue to the public.

"Because Somebody Talked," by Wesley Heyman, c. 1944.

This poster, created in 1944, was one of the few non-solicited poster designs. Relatively unknown artist Wesley Heyman created the poster. This poster’s production numbered in the millions; requests for it broke all previous records.

Brick Store Museum Collection

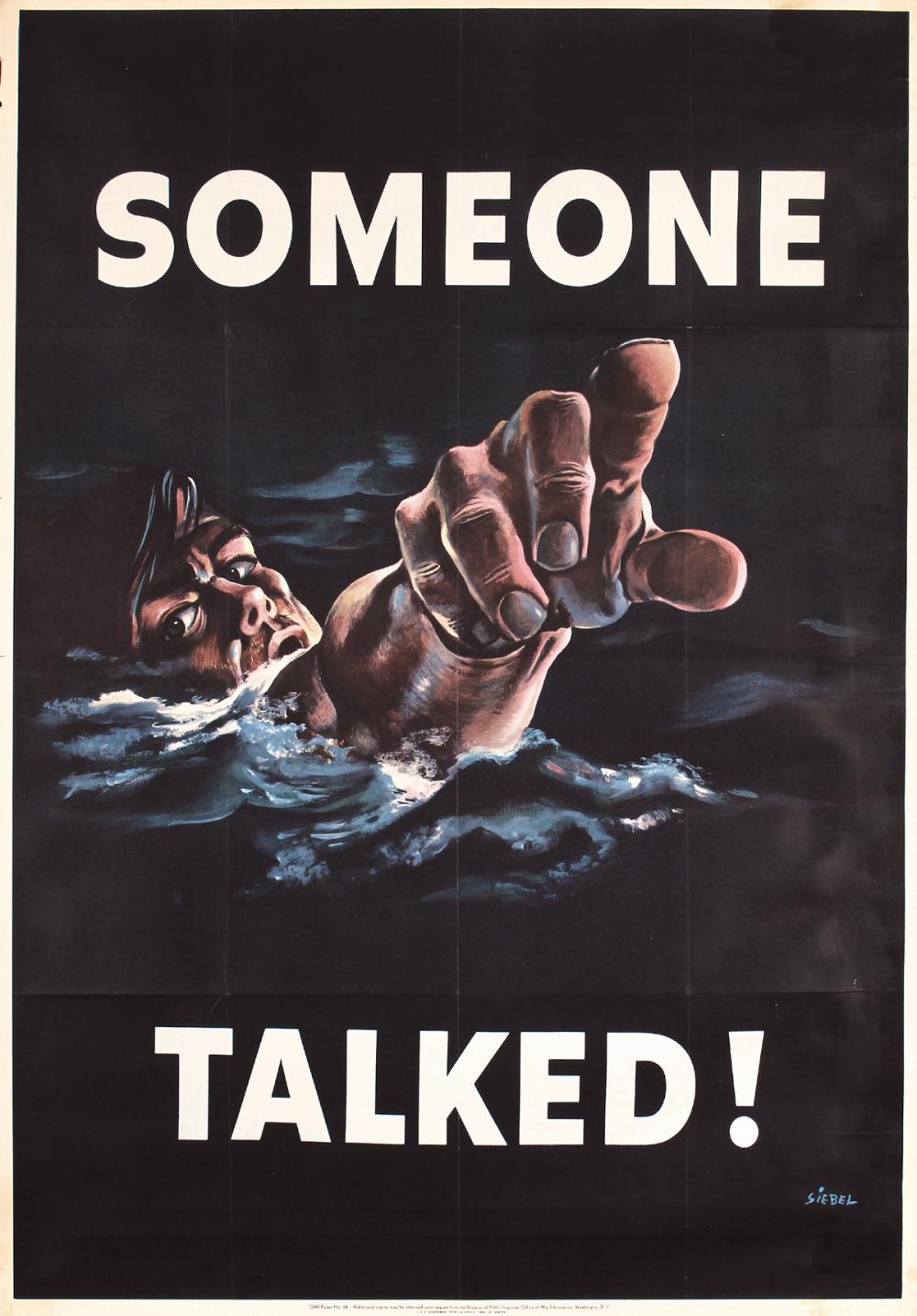

"Someone Talked," by Frederick Siebel, c. 1942

OWI officials felt that the most urgent problem on the home front was the careless leaking of sensitive information that could be picked up by spies. Posters were not subtle in reminding citizens what might happen due to their careless talk. Frederick Siebel immigrated from (then) Czechosolvakia in 1913, and joined the U.S. Army in 1942.

Brick Store Museum Collection

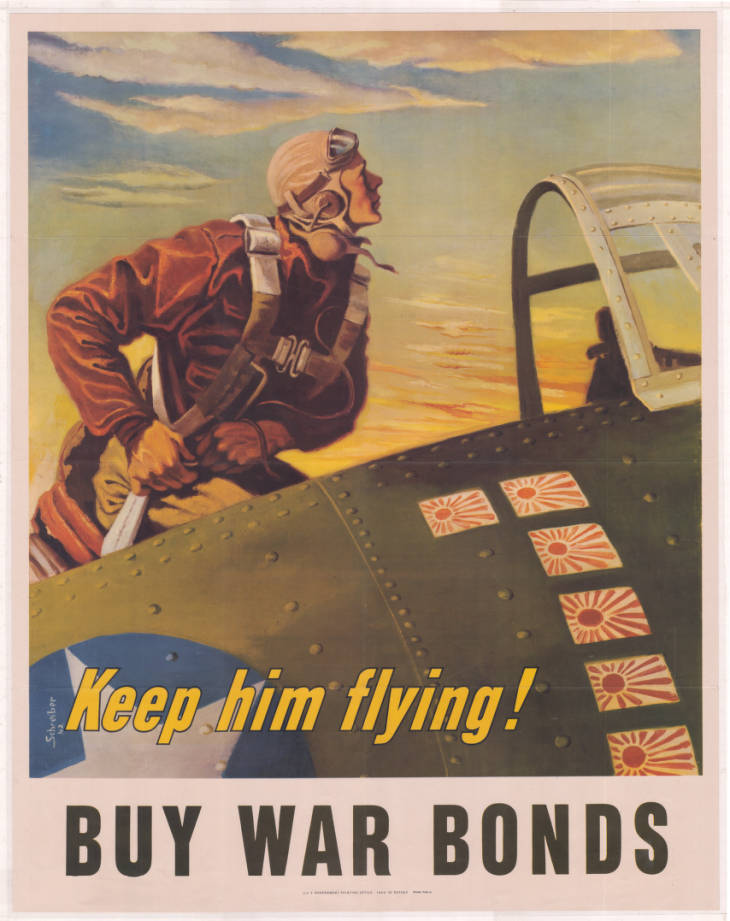

"Keep Him Flying!"

As opposed to World War I’s heavy sales of Liberty Loans, the U.S. Treasury and OWI aimed to secure the widespread ownership of public debt.

From January 1, 1941 to January 1, 1942, Kennebunk citizens purchased $68,850.00 worth of savings bonds. Adjusted for inflation, that equals over $1,035,000.00 today.

Brick Store Museum Collection

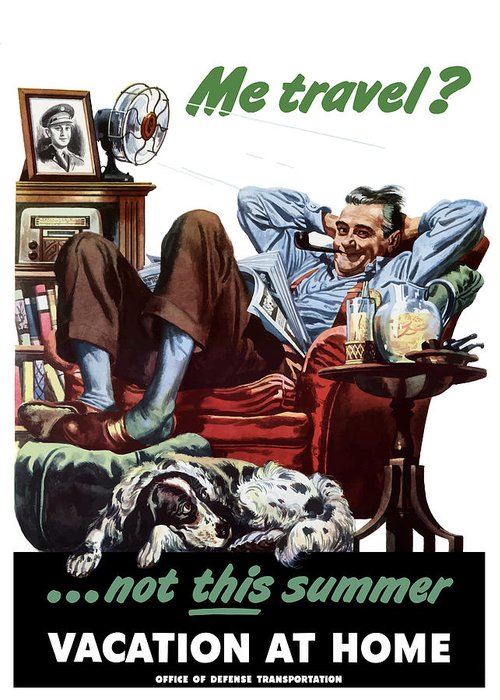

"Vacation at Home"

In 1942, it was announced that no Mainer could purchase new tires unless they held a special certificate. This gave many a reason to stay at home instead of travel.

Brick Store Museum Collection

Kennebunk Prepares for War

Kennebunk prepared for war like many towns across the nation did. Kennebunkers were active as air raid observers – in 1942, Chief observer Carle Spiller required at least 35 women to join the corps of 35 men. These observers reported for two hours of duty to watch for the approach of airplanes. One of Kennebunk’s observation stations stood at what is now the I-95 overpass on Cat Mousam Road; the other atop the Pythian Block building on Main Street. In other preparation efforts, the Public Health Association, in search of places for an emergency hospital, selected the Webhannet Golf Course’s clubhouse. Beach patrols on the town’s beaches saw citizens watching for enemy approach by water. By the end of the war, there were several known German U-boats off the coast of Maine.

Blackout!

By order of the U.S. government, all illuminated window signs, flood lighting, store window lighting, or any other type of display lighting visible from the outside was required to be extinguished from sunset to sunrise. Lights at night endangered American towns at risk for attack from the air or sea. Enemy planes or ships were able to pinpoint civilian locations by looking for lights in the darkness. To prevent this, the government ordered all civilians to be on alert. When the signal sounded, all light was to be extinguished immediately.

During the blackouts, lights were permitted in rooms that were equipped for a blackout, so that no light was visible from the outside. Many families had heavy window shades or curtains that blocked the light.

The ban on lighting included hospitals, first aid stations, hotels, apartment houses, and railroad stations. No vehicles were allowed to operate during the blackout, and all street lights were extinguished. Should you be driving during the signal, you were required to pull over and turn off your lights.

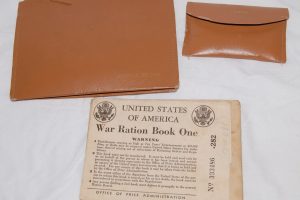

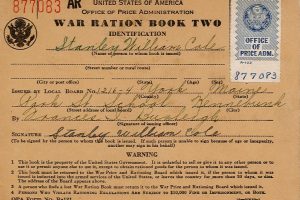

Your Fair Share

The U.S. government formed several oversight organizations to help educate and organize civilians in their duties during the war, especially regarding food, conservation, and rationing. The War Ration Board was established in 1942. Every town – including Kennebunk – had one, which allowed civilians to register for ration stamps for meat, fuel, sugar, flour, and much more. Kennebunk native George Wentworth managed the rationing board in York County.

Rationing meant that Americans had to get creative with their cooking! Sugarless cookies, eggless cakes, and meatless meals were the order of the day. With less food to go around, the U.S. government guaranteed that everyone get their share of the food and fuel by giving out ration stamps.

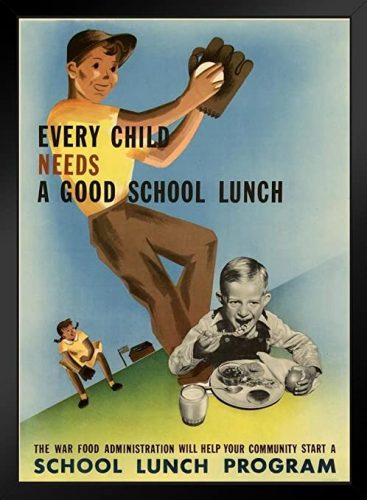

The War Food Administration formed in 1943 to direct the production and distribution of food to meet war and essential civilian needs. The office determined the amount of food available for civilian use, and rationed it to make sure that everyone received their fair share. Posters like those in this exhibit helped to emphasize the link between rationing and the war effort.

Did You Know?

Rationing and Victory Gardens started in World War I, although both are more known for their roles in World War II.

How Rationing Worked

Rationing existed to make sure that all Americans received their “fair share” after the demands of the military were supplied. Without rationing, a war-short supply would soon be depleted by a few people, as opposed to everyone getting some. Sugar was one of the first consumer goods to be rationed during the war, though it would come to include such items as coffee, meat, butter, tires, and gasoline.

Because of the demands on farmers and food manufacturers by the military, prices for everyday items rose. To combat the rise in cost, the government instituted top legal prices for each “everyday” food item, and required restaurants, groceries, and other food service locations to report on their costs for each category of food.

Ration books were awarded to every individual of a household (including babies). It was up to the homemaker (usually the mother) to pool the stamps and plan the family’s meals within the set limits of what she could buy with the stamps. Kennebunk and other towns held registration days in order to get a proper count of the amount of ration books needed. There were five registration centers in Kennebunk: four elementary schools and Town Hall. If you missed registration day, then you had to wait until the next month. These ration stamps proved a person was eligible to receive such goods.

Ration Artifacts (click to zoom in)

- Ration Book, leather holder, and token purse. Brick Store Museum Collection.

- Ration tokens and token purse, Brick Store Museum Collection.

- Sugar Ration Card from 18 Pleasant Street, Brick Store Museum Collection.

- Sugar Ration Card from 18 Pleasant Street, Brick Store Museum Collection.

- Sugar Ration Card from 18 Pleasant Street, Brick Store Museum Collection.

The government was aware of the dangers of price increase due to war; the country had just experienced this effect twenty-five years earlier. To defeat this issue, the U.S. Office of Price Administration kept tabs on prices.

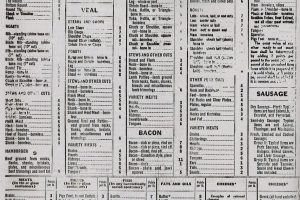

Chicken was more expensive than beef in the 1940s. Chicken producers were required by law to divert the majority of their produce to the military – product scarcity drove prices up. Military and government orders on chicken and turkey demanded almost 250 million pounds of these meats in 1945 alone!

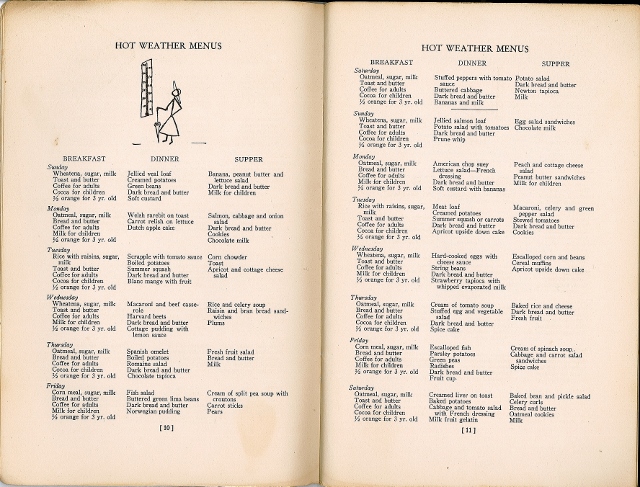

At left, a list of menus printed in “Low Cost Food for Health,” c. 1944. Brick Store Museum Collection.

Blue Points and Red Points

Each person started with 48 blue points (processed foods) and 64 red points (meat, fish, and dairy) each month. For every month, a new set of ration stamps were handed out as the old ones expired. Each stamp had a number on it to designate the points it was worth, as well as a letter showing for which “rationing period” the stamp could be used.

Each rationed product had a point value assigned to it that was independent of the price. The point value could fluctuate depending on scarcity and grocers were required to keep current official point lists posted. At the checkout counter, the shopper was to remove the proper amount of stamps in the presence of the clerk. Point management was critical to effective shopping since the number of points available was limited by the rationing period. By 1944, evolving regulations resulted in a simplified plan that introduced one point tokens to be given as change.

But what does that mean?

When buying food at the market (or anywhere else that required ration stamps were required), shoppers approached the check-out counter with both money and ration stamps. The grocer would ring up the purchases, and give a dollar amount plus a stamp amount needed to purchase the rationed items. Shoppers would then receive their change back in both cash and stamps (or tokens if the stamp “change” was less than a dollar).

For instance, you are at the market purchasing steak, juice, eggs, and flour. The grocer tells you the total is $9.60, but he also tells you that for the steak, eggs, and flour, that is $4.60 in meat ration points (stamps often ranged from $1 to $5 increments), and $2.00 in flour ration points. You could hand him a $10.00 bill, and take out your ration book to tear out $5.00 worth of meat ration stamps, and $2.00 worth of flour ration stamps. The grocer would hand you .40 cents in coin change, and .40 cents in tokens for the unused meat ration points. If you didn’t have enough stamps to cover the total needed, you couldn’t buy it. Lost stamp books were a headache for those that misplaced them. Even if you had money, you couldn’t buy rationed goods without the stamps.

From the Archives (click to zoom)

- Ration Book Two, owned by WIlliam Cole of Kennebunk. Brick Store Museum Collection.

- Ration points inside Ration Book. Brick Store Museum Collection.

- Rationing Table, c. 1945. Brick Store Museum Collection.

What about restaurants?

All food establishments, including restaurants, hospitals, and schools were also subject to rationing, but did not use ration books like civilian homes. Customers would pay money for meals, but not use ration stamps. Food service issues included labor shortages, “meat fixing” (the best cuts went to fancy hotels, not supermarkets), and slower business overall (fewer families could afford to eat out).

Restaurants were required to file their menu with the Local War Price and Rationing Board. Owners listed items on their menus that appeared on a list of “40 basic items.” Ceiling prices were created to make sure that no consumer was paying more than their fair share.

The Kitchen in Wartime

During peacetime, 100% of food went to civilians. During the war, 75% of the supply went to civilians, 13% to the armed forces, and 10% to allied nations. Everyone had to make their meals stretch the week – often practicing conservation techniques like “meatless dinners.” Citizens in Kennebunk and throughout the nation were encouraged to install Victory Gardens in their back yards to supplement these rationed goods. Whatever you grew, you could keep.

In addition to growing their own vegetables, Kennebunk citizens also went clamming, fishing, and hunting to add to their family’s food supply. Dandelion greens and berries were also plentiful in fields. Farmers that owned chickens sold the majority of their eggs to the government for the war effort; but would sell cracked eggs (the kind that we throw away today) to citizens who ran out of ration stamps.

The kitchen became a source for war production – at home, that is. Because electric refrigerators were just becoming popular, they were very expensive, and most people in Kennebunk didn’t own one. The metal used to make these refrigerators was also rationed – most metal went straight to the war, so not many refrigerators were made during this time. So, what did people use to keep food cool? Iceboxes! Ice delivery would occur every day in the summer months, and less frequently during the winter.

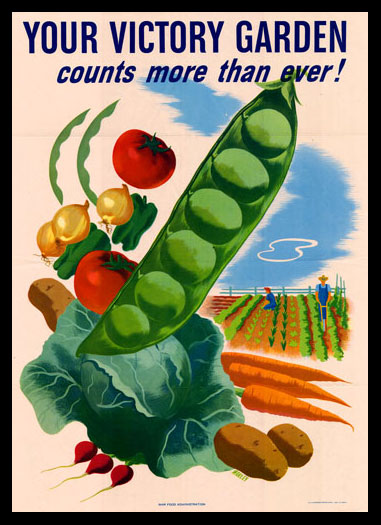

Victory Gardens and Farms

Victory Gardeners produced over 10 billion pounds of food in 1943 alone, over one-third of all fresh vegetables in the country.

The government recommended that fresh fruits and vegetables be canned for use throughout the year.

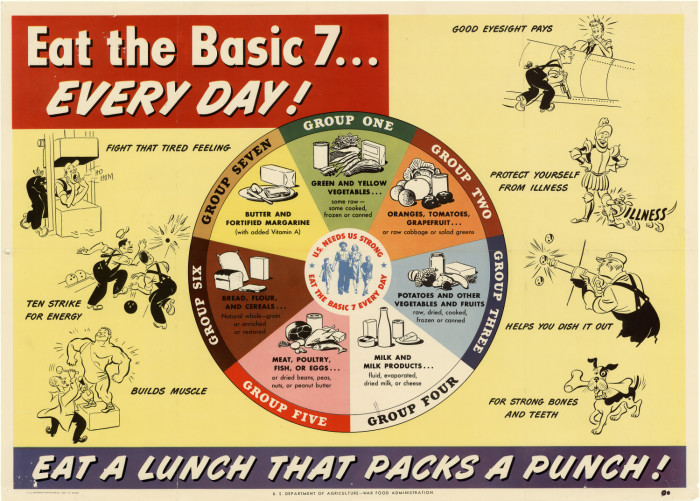

Citizens were encouraged to “eat the basic 7” every day,” and substitute for foods that were scarce. Families were asked to buy only what they needed; use everything they bought, including leftovers.

Make It Do Or Do Without

Home front Conservation

To ensure that there would be plenty of goods for the military effort, the government launched a conservation campaign. Everyone became a part of the war effort as they conserved fuel, food, water, materials, and time. The working population was even charged to attend work every day because absenteeism might give an advantage to the enemy.

Communities, including Kennebunk, held scrap and salvage drives. Pots, pans, shoes, and tires are just some of the things they donated to the war effort. Everyday items like metal, rubber, nylon stockings, and even meat fats were conserved by every American to turn into fighting materials. American companies halted production of “big ticket” items like washing machines, refrigerators, ice boxes, cars, and anything with metal. Families would use what they had until the end of the war. When word got out that Nichols’ store in downtown Kennebunk had women’s stockings in early 1945, women waited in line to purchase them. Children were expected to take part in the effort, too. The collection of tin cans, tin foil, and other metal scraps often fell to children, who would roll the scraps into a ball. Once the ball got big enough, it was turned in downtown.

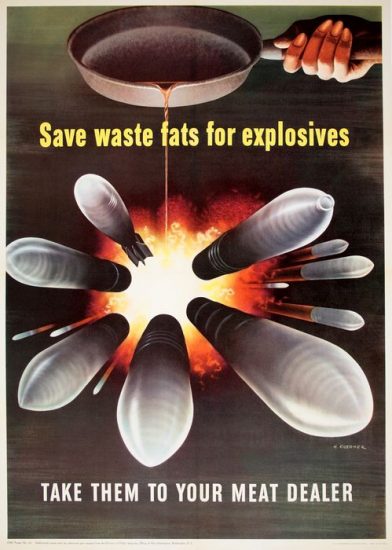

“Save Waste Fats for Explosives,” c. 1944. Brick Store Museum Collection.

About the artist: Henry Koerner (1915-1991) was an Austrian-born American artist. As a Jewish man, he departed his home country in 1938 after Hitler came to power, leaving behind his parents and brother. Koerner is best known for his TIME Magazine portrait covers. In 1944, he was drafted into the Army, and assigned to the Graphics Division of the Office of Strategic Services, where he produced war posters like “Save Waste Fats.” After VE Day in 1945, he was dispatched to Germany to sketch defendants at the Nuremberg war trials. A year later, he discovered that his parents and brother had been killed in an extermination camp.

What did the government use these materials for?

- Silk (parachutes): women often drew lines on the back of their legs to have the appearance of wearing hosiery.

- Rubber and metal (military transports, armament, uniforms, boots): citizens were asked not to travel, as you only had four tires to use throughout the war! Cars were not produced during that time, either. Bread almost never came sliced – the slicing instrument could not be replaced due to the metal shortage.

- Meat fats (ammunition): As butter, meats, and oils were already rationed, women re-used cooking fats as often as possible before turning it in to be used for the war.

Through posters, news articles, the radio, and word of mouth, Kennebunkers and other citizens heard a lot about shortages during the war. To prevent mass panic, the War Production Board often had to set the record straight, and advise citizens on the best plan of action. In 1943, a rumor about the shortage of soap inspired local women to start making their own. In doing, they began to hamper the war effort – valuable glycerin was lost when soap was made at home. The Kennebunk Star urged women at home to “say ‘no’ to rumors.”

Aside from printing posters to inspire the war effort, the U.S. government also printed hundreds of pamphlets, booklets, articles, and brochures to help homemakers and families make do with less.

What Did We Learn?

August 14, 1945:

The news of Japan’s surrender reached Kennebunk, and within minutes of the radio announcement, Main Street was filled with jubilant crowds for over two hours. It was estimated by the Kennebunk Star that over 2000 people took part in the celebration. Church bells rang, fire sirens went off, and cars were decorated. One vehicle even dragged a dummy behind it, labeled “Hirohito.” At 9pm there was a service at the Baptist Church, drawing about 100 attendees. Local man Michael Burke was injured that evening during the celebrations; he was hit in the head by someone throwing a large piece of cement from a balcony.

Food issues have been a constant in our history. Whether we have too much, too little, or none at all, our culture is often driven to success or failure by the food that we eat. In the case of America’s war effort in the 1940s, food was considered as much a weapon as any other armament. The war was not easy for anyone. Many millions of people lost their lives.

Today’s study of World War II is an important one; not only does it demonstrate how a country can pull together, but how we can all learn from mistakes and successes of the past.