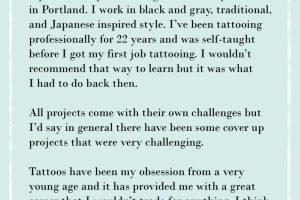

What does “tattoo” mean? The word describes the process of inserting pigments under the skin using a needle (or sometimes something else) in order to produce an indelible mark that is visible through the layers of skin.

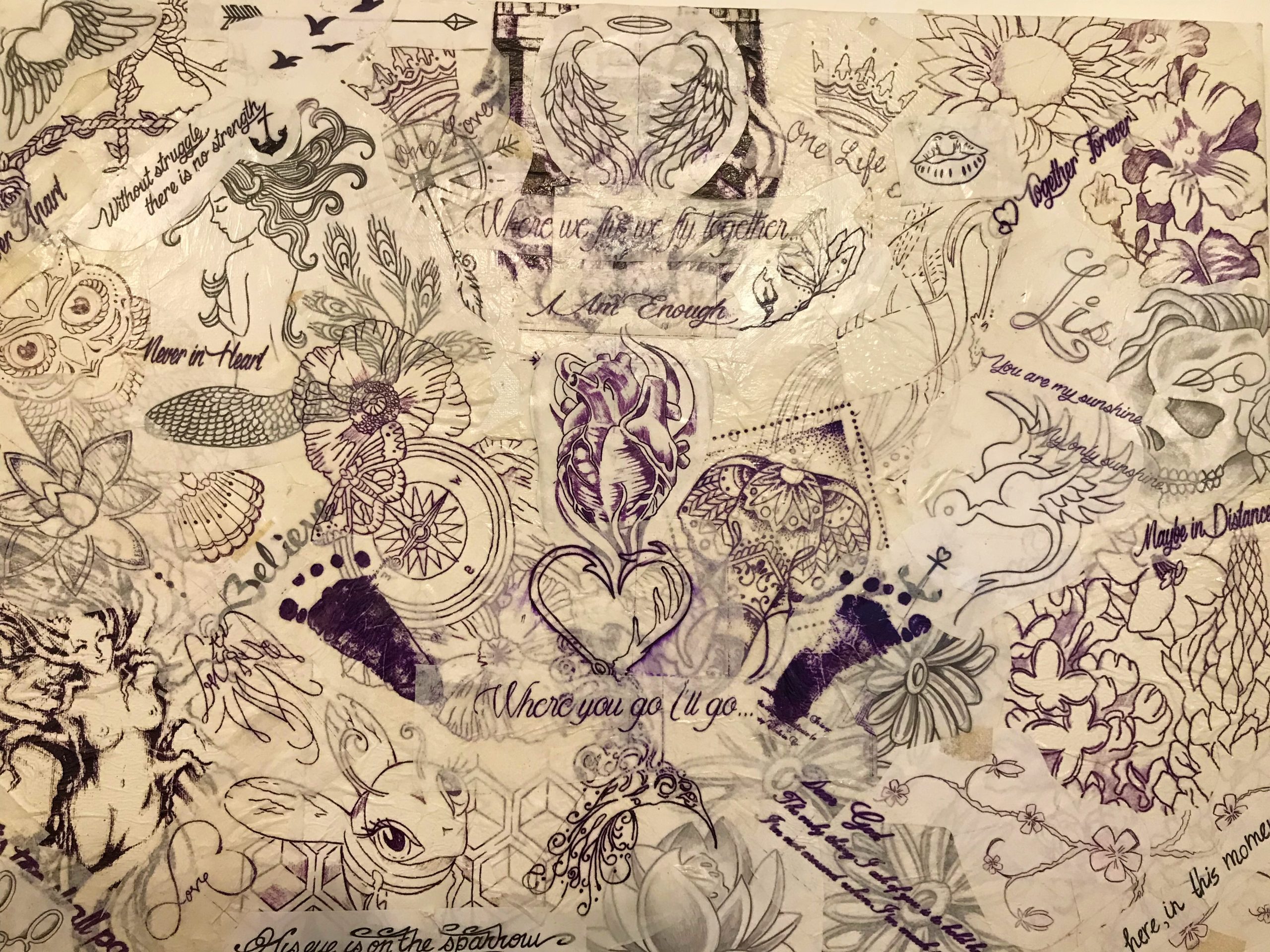

Their meanings, however, are more storied and vary greatly from memorials, inspirations, family heritage, art and cultures. Every tattoo holds a story.

In this virtual exhibition, we will explore the history of American tattooing and its evolution into modern artistry, as showcased by artists and clients here in Maine.

HISTORY

The practice of marking skin with ink is over 5,000 years old, practiced in every part of the world and on both males and females. These designs, intended to be permanent, serve a variety of roles dependent on the “wearer.”

The earliest evidence of a tattoo on a body comes from the 5,200 year-old Iceman, found on the Italian-Austrian border in 1991. His tattoo patterns across his spine, knee and ankle joints suggest that the practice had been used therapeutically. Previous to this discovery, it was known that ancient Egyptians’ tattooing was an exclusively female practice for about 1,000 years. Recent studies assert that this female custom arose to safeguard women’s pregnancies, both therapeutically and as an amulet during childbirth.

Examples of tattooed ancient peoples have been found the world over. Mummified remains in Siberia, Peru, the British Isles, Scandinavia, Italy, Greece, China, Japan, and indigenous America (to name a few) all show that tattooing was common in many cultures. Often, cultural traditions from namely Polynesia and Egypt show that women only (not men) received tattoos as a sacred rite.

Current historical theory deems the practice of tattooing to have sprung up independently in various cultures. First tattoos appeared to place protective or therapeutic symbols upon the body, and later as a means of marking people out in various social groups, to today’s self-expression using tattoos as art.

American Tattooing

Although the ancient peoples of Europe had practiced some forms of tattooing, the practice had largely disappeared before the mid-1700s. As Europe and the United States expanded their trade routes in the 18th and 19th centuries, sailors’ exposure to cultural tattooing especially in the Pacific region saw travelers return home with their own tattoos. The ink markings were especially popular with sailors and coal-miners because those were incredibly dangerous jobs, and the amulet-like use of anchors or a miner’s lamp on men’s forearms soon became the oft-repeated symbols of tattooing.

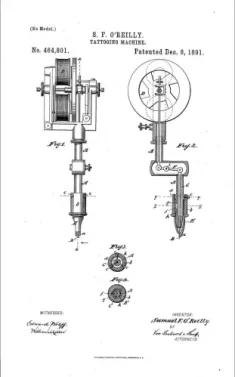

The American Industrial Age of the mid-19th century brought technological advances in machinery and new colors, leading to a uniquely American mass-produced form of tattoo. These new advances mirrored the original intent of Polynesian tattooing: to show loyalty and devotion, to commemorate a great feat in battle, or simply beautify the body.

One of the first permanent tattoo shops was founded by Martin Hildebrandt in New York City in 1846. His habit of tattooing soldiers and sailors became an institution during the Civil War. The practice grew among sailors and soldiers, especially because they were a way for soldiers to guarantee their bodies would be identified in the event of death. Popular designs included military insignia and names of family members.

However, the American aristocracy generally looked down on tattoos. Ward McAllister, an 1890s aristocrat, once said, “It is certainly the most vulgar and barbarous habit the eccentric mind of fashion ever invented. It may do for an illiterate seaman, but hardly for an aristocrat.” While Europeans accepted tattooing in a variety of forms, Americans understood tattoos in a different way.

For this reason, the military served as the main artery to popularizing American tattooing. Its Golden Age came during World War II, due to the general patriotic mood of the country and the massive amount of military servicemembers in the 1940s (nearly 10% of the population). By the 1950s, tattooing had an established place in American society, but was still generally disdained by the majority.

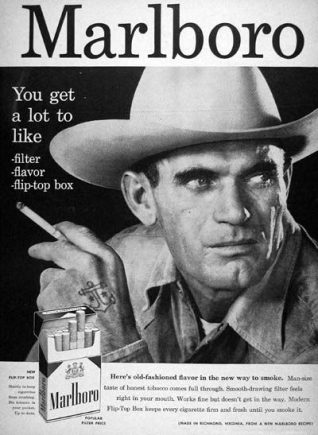

Tattooing’s relationship to masculinity helped push the trend further. As World War II veterans were (deservingly) lauded as heroes after the war ended, they re-entered the workforce. Tattoos became a part of the “masculine” heroic image of the 1950s, which many would take to heart. Evidence of this is shown by symbols of American “manliness” at the time, such as the Marlboro Man and the sailor cartoon Popeye. Both sported tattoos related to military service.

In the 1960s, a Hepatitis outbreak in New York City was blamed on a Coney Island tattoo shop. Whether or not it was true, this case fueled the nation’s continual denial of tattoo artists and tattooed people as legitimate in American society. Tattooing was banned in New York City from 1961 to 1997; and in Norfolk, Virginia from 1950 to 2006 for being unsanitary and “vulgar.”

Cultural Revitalization

The 1970s marked the first decade in which tattoos were embraced by people other than mostly veterans and sailors. The countercultural movement led by young generations drove people to get permanent proof of their commitment to the ideals of the decade. Peace signs and other symbology were popular; but tattooing remained on the outskirts of mainstream acceptance.

American culture in the 1980s reimagined almost every aesthetic, including clothing, hair, gendered styling, design and music. The rise of rock & roll bands whose stars sported heavy tattoos inspired fans to do the same. Next came the punk movement in the 1990s, in which wild hair colors, piercings and tattoos played a large role in self-expression. At this time, plastic surgery also became more widely accessible, so that body-modification no longer seemed so strange. By 1996, it was estimated that nearly half of the people seeking tattoos were women, signifying a major shift in how tattoos were accepted.

The transformation of tattoos and their uses (and who got them) is a key example in how most societal structures evolve and broaden over time.

Perspectives

Today

Nearly 95 million people a year get a tattoo. In 2019, 40% of Americans reported having at least one tattoo, an increase from 21% in 2012. Those under 55 years old are twice as likely to have a tattoo – 40% of those ages 18 – 54 have a tattoo; while that number falls to only 16% of those 55 years and older. Of those 18 – 35, nearly half (47%) have tattoos.

The average number of tattoos Americans report having is four. By 2014, slightly more women than men reported having at least one tattoo, though results may have been skewed due to the inclusion of “permanent makeup” tattoos.

Changes Over Time

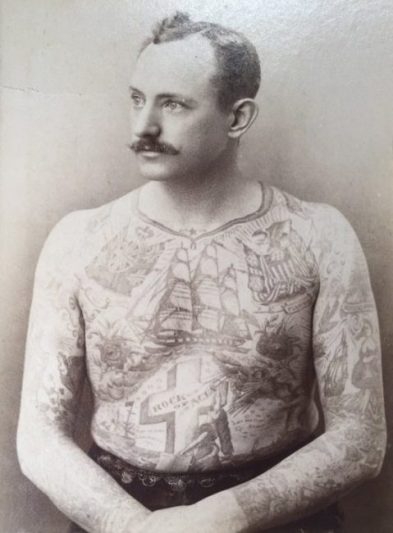

At the turn of the 20th century, people covered with tattoos became attractions. Freak shows and circuses boasted tattooed men and women for people to see. Nora Hildebrandt was one of the first tattooed women to gain fame like this, her contract beginning in 1882. Historians have speculated the reason so many women agreed to be tattooed head-to-toe was for their own independence; Nora Hildebrandt was paid $100 per week, the equivalent of $2,600 weekly today.

Tattoos as Art

Today, tattoos and their creators are increasingly seen as another art form. Now that the long road to tattoo “acceptance” has been paved, the focus has now turned to artistic quality. Social media, particularly Instagram, has played a large role as a platform for tattoo shops and artists to display their work and reach wider audiences (before, it literally walked away and was hidden under clothing!).

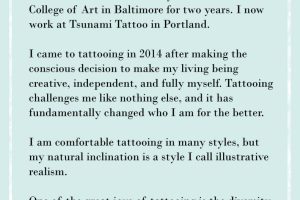

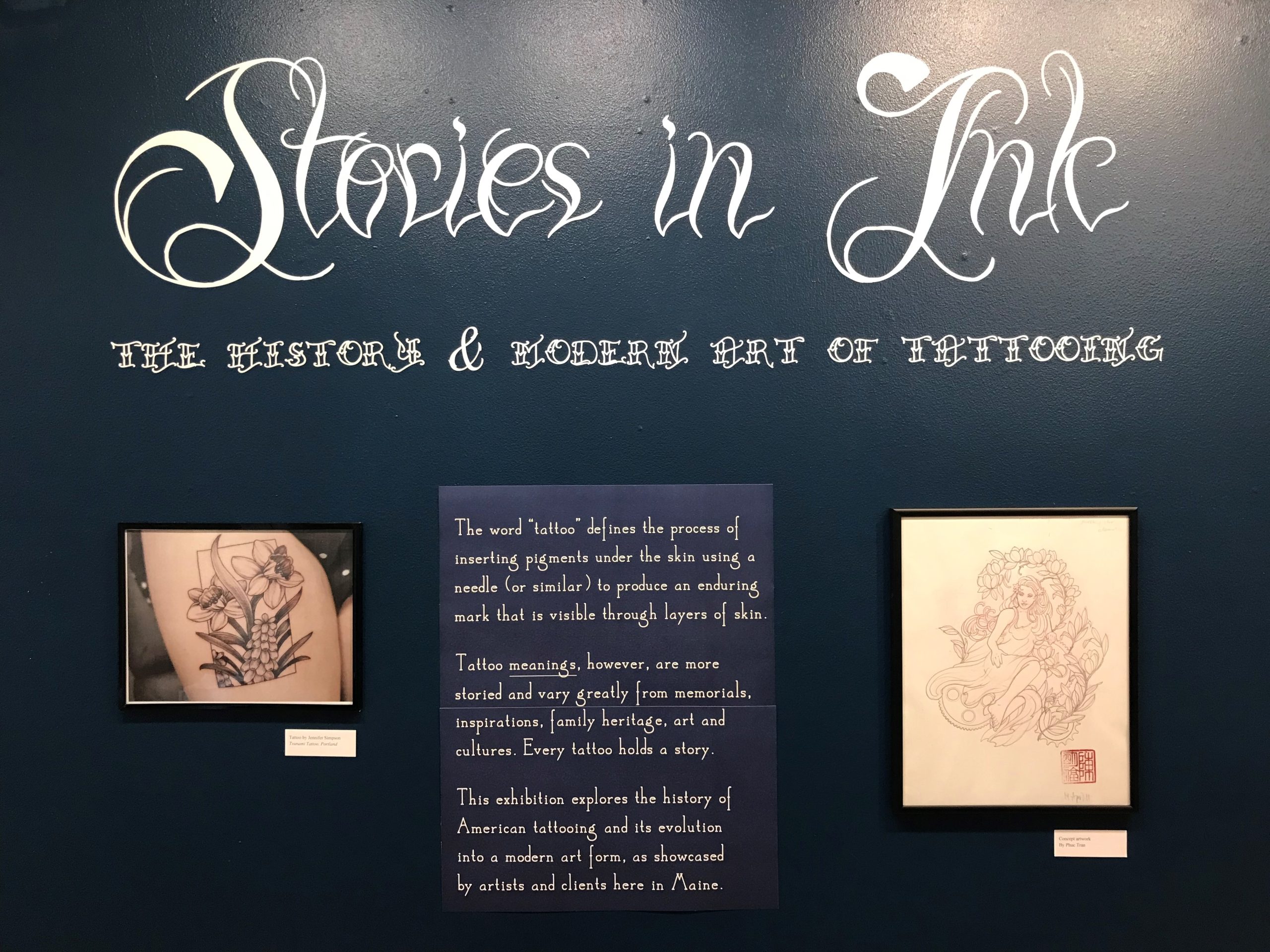

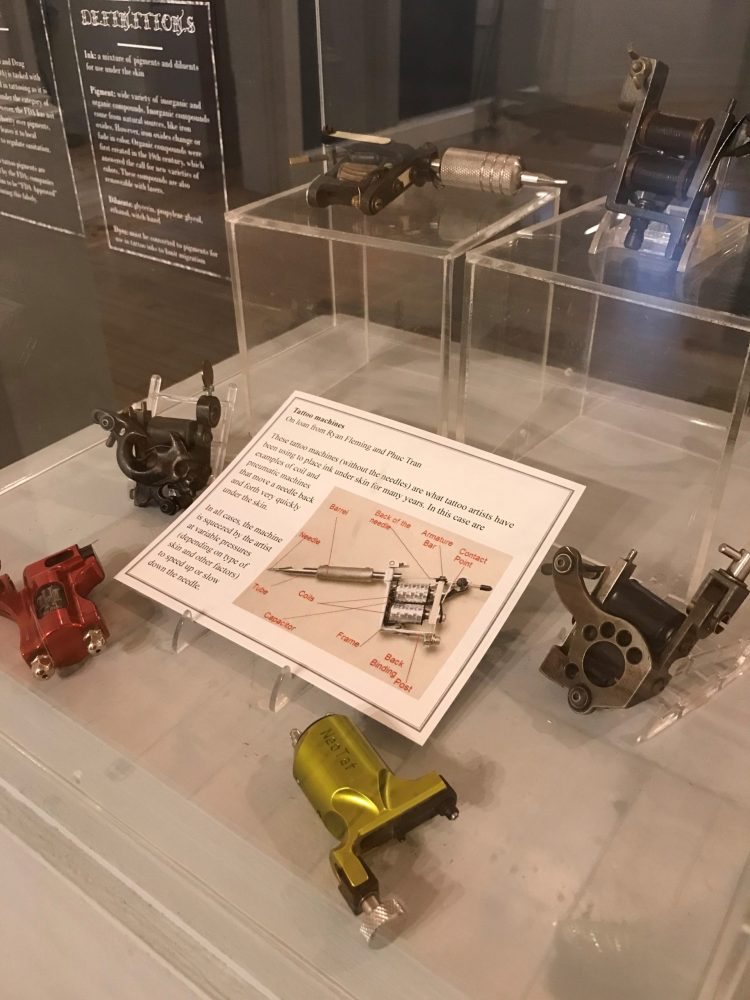

In the past 15 years, the process of tattooing has sped up in various ways, including technologically advanced machines to respond to the varying needs of artists, like different frequencies of needle vibration for areas of the skin and safe needles. In addition to technological changes, another theme has appeared: many tattoo artists are art school graduates. Owning (or working in) a tattoo shop provides a steady career path for those graduating as artists.

Scenes from the 2021 Exhibition

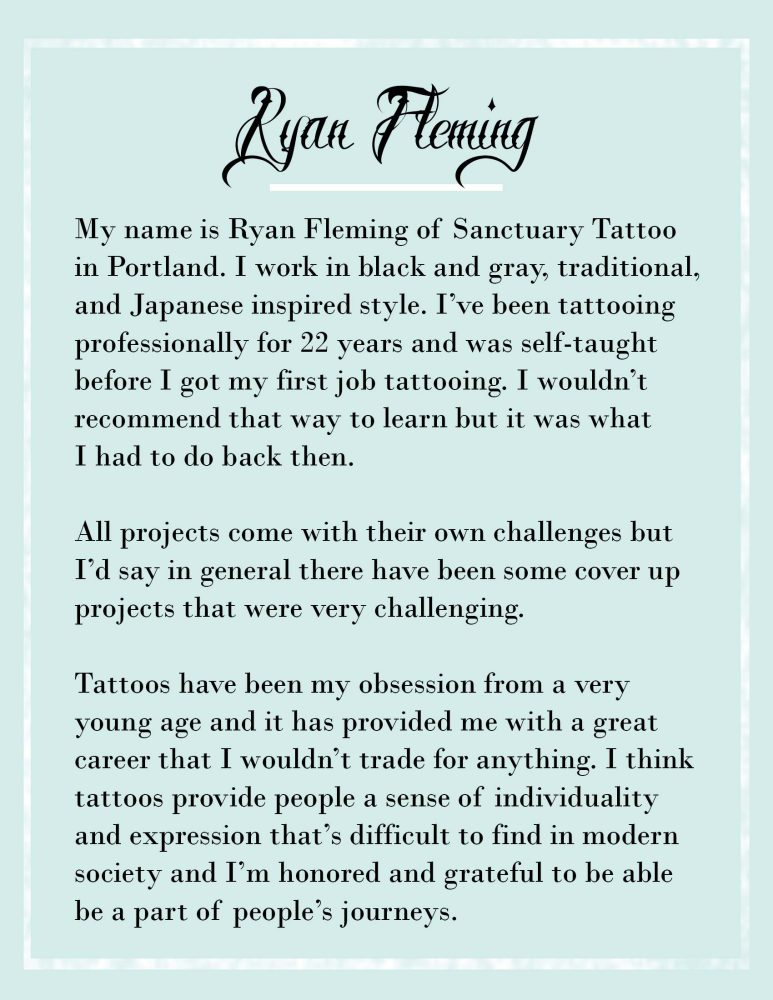

- Ryan Fleming artwork, courtesy Ryan Fleming

- Ryan Fleming artwork, courtesy Ryan Fleming

- Tattoo machines, courtesy Ryan Fleming and Phuc Tran

- Contemporary Tattoo Showcase inside exhibition, courtesy Ryan Fleming, Phuc Tran, Jennifer Simpson and Justin Melton

- "Let It Flow,", courtesy Justin Melton

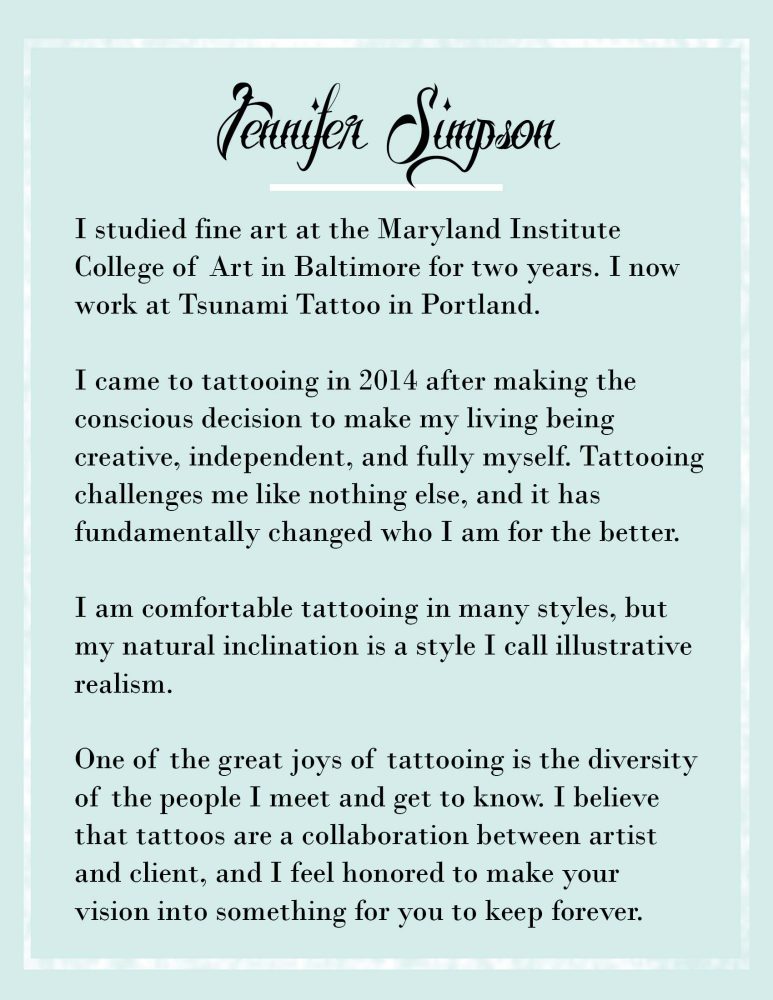

- Tattoo artwork, courtesy Jennifer Simpson (L) and Phuc Tran (R)

Meaning & Imagery

Tattoos are arguably the most personal visual expressions of someone’s life and its meaning(s). Much like artwork on canvas, it can convey meaning without many words attached. But unlike artwork, jewelry, or even clothing as a means of visual expression, these ink designs are permanent fixtures on your body.

Why do people get tattoos?

There are many reasons why someone gets a tattoo, including:

- Decoration: personal enjoyment, or identifying with a certain group (i.e. military, cultural, club, etc.)

- Identification: prisoners (in current prisons, or concentration camps, for example)

- Personal proclamations: love, memory, fandoms

- Cosmetic purposes: permanent makeup, cancer reconstruction, covering bodily traumas and scars

In any case, tattoos carry strong personal emotions that reflect a person’s inner feelings and personality. These markings are a form of individual communication; unspoken visible messages that convey various details of someone’s life, experiences and beliefs.

Cultural anthropologist Margo DeMello studied what she called the “self-help tattoo,” which reflected self-awareness, expression and life improvement – almost like a form of therapy.

Tattoo Psychology

In 2021, psychologists with the Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System studied the relationship between tattooing and the psyche, to learn how skin art can inform mental health treatment for patients.

They found that although the acceptance of tattoos is expanding, tattoos remain most common in the groups traditionally associated with the practice: for example, 65% of those in the military report having at least one tattoo.

Tracing the evolution of tattooing from its tribal origins through to the World Wars and subsequent mainstream inclusion, the psychologists wrote that tattoos could be viewed as a psychological support aimed to bolster “self-image, inspire hope, keep noxious emotions at bay, and reduce discrepancy between the individual and his aspirations.” They also highlighted the use of tattooing when people feel unable to adequately verbalize feelings, memories and emotions for a variety of reasons. In their study, they noted that respondents tended to view their tattoos as a means of self-distinction with significant personal meaning, as opposed to symbols of rebelliousness. Interestingly, one study showed that those with body modifications (tattoos included) were more likely to take part in social and healthy behaviors.

Tattoos also come with a certain amount of physical pain. Local Maine tattoo artists noted that sometimes they will see repeat-clients who are somewhat less interested in the tattoo’s image, and more needing of the process and pain of tattooing to allow for a release. Pain is just one way that humans feel they can release their emotions.

Tattoo Styles

The following are examples of the variety of tattoo styles that exist today:

American Traditional

(also called Old School) popularized in the 1940s by artist Norman Collins (aka Sailor Jerry). Collins combined what he learned from American, European and Japanese tattooing to establish this new style. It is known for clean black outlines, vivid colors and minimal shading.

Realism

though classical art realism has existed since the Renaissance, realism in tattoos became popular in the latter 20th century with its refined designs that depict authentic-looking portraits, nature, landscapes, and everything in between.

Watercolor

the 21st century has seen a boom in this modern style. It is what it sounds like: a tattoo as if rendered with a brush and watery pastels. While it appears fairly simple, this style is very hard to accomplish with ink on skin.

Tribal

Indigenous body art is frequently referred to under the umbrella term “tribal.” There are multiple styles depending on the community from which it originated. Imagery often represents life stories and family. Each style is unique, and are often done in black ink with elaborate patterns.

New School

This style came to prominence in the late 1980s and early 90s. It features a highly animated aesthetic that takes after pop culture in that period of time. The style can be described as cartoonish or exaggerated in nature.

Neo Traditional

an evolution of the American Traditional style. Still with pronounced lines and vibrant colors, this style also showcases illustration and is highly influenced by Art Nouveau and Art Deco aesthetics. Imagery depicted is often of florals or animals.

Irezumi

this traditional Japanese style originated during the Edo period (1603-1868) alongside woodblock prints. They were hugely popular amongst the working class, and often represented age-old folklore (such as dragons and phoenixes).

Blackwork

a very broad category which applies to a variety of work created solely using black ink. This includes geometric and ornamental designs, or detailed illustrative pieces. This style is currently experiencing a lot of artistic experimentation in the tattoo industry.

Illustrative

From etching to abstract to calligraphy, this style is versatile. Many artists who work in this style blend their own aesthetic with it to create a whole new style of their own. Generally, if a tattoo looks like it belongs on a wall or hanging in a gallery…it’s Illustrative!

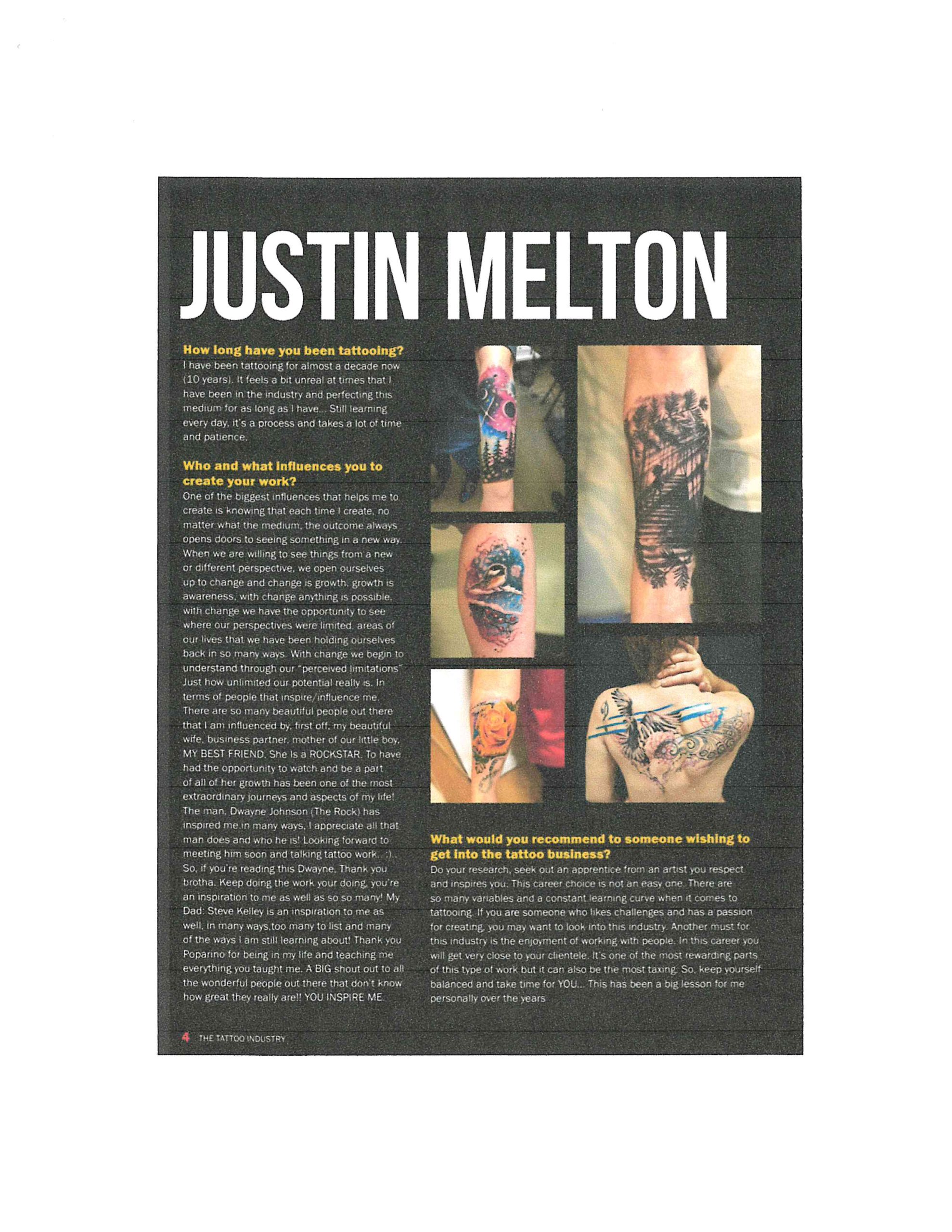

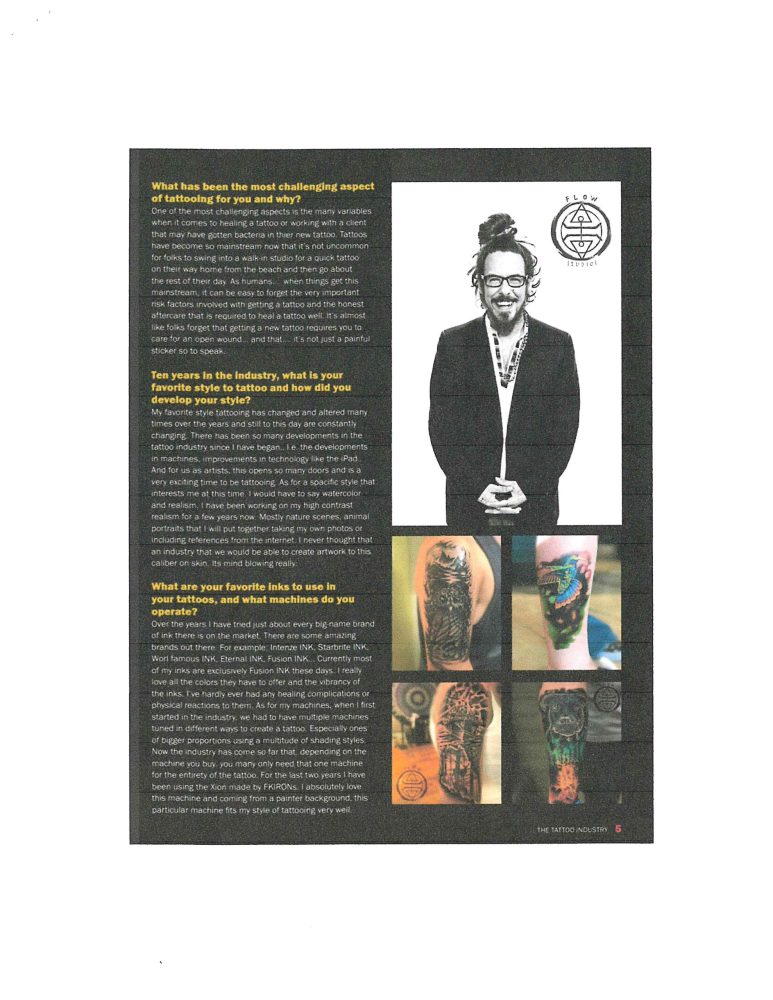

Interview with Justin Melton

This is a pre-recorded interview with Justin Melton, owner/artist at Flow Studios in Kennebunk, Maine.

How a Tattoo is Created

This is a time-lapse video by artist Jennifer Simpson (Tsunami Tattoo, Portland) showing how she created a crow tattoo for a customer using photographs, hand-sketching and computer-aided design.

Thank you!

The Museum wishes to thank the following individuals for sharing their skills, knowledge, artwork and passion with us:

Justin & Marissa Melton (Flow Studios)

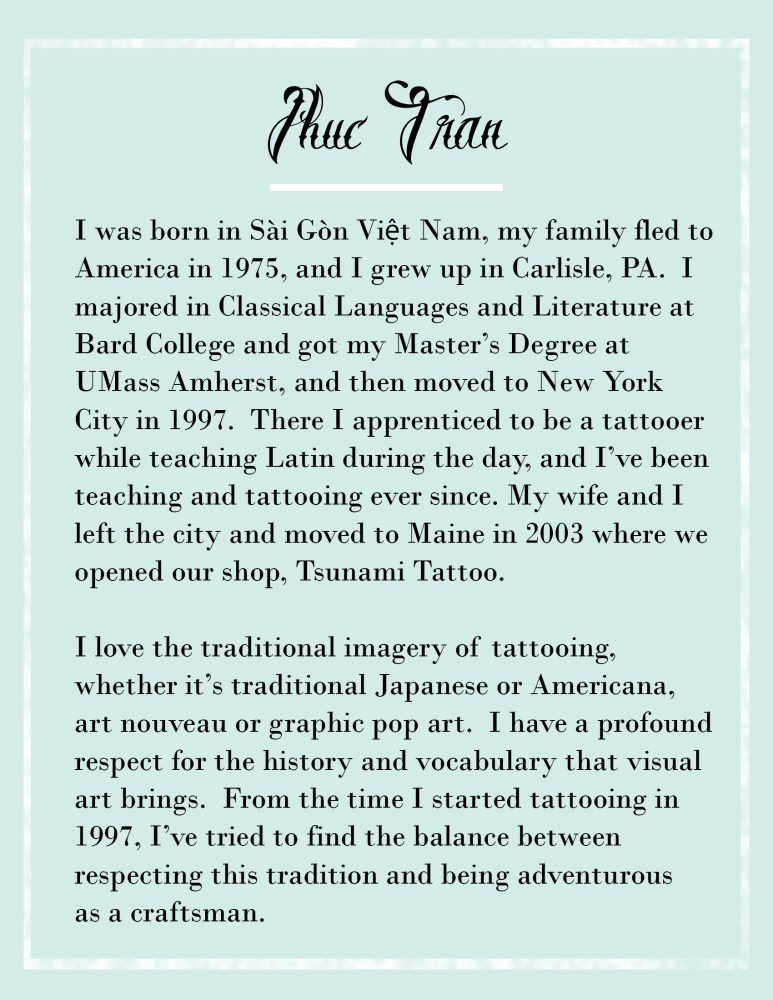

Phuc Tran (Tsunami Tattoo)

Ryan Fleming (Sanctuary Tattoo)

Jennifer Simpson (Tsunami Tattoo)

SaShell N.

Matt C.

Danielle F.