What are Weirs?

Fish weirs are inter-tidal or riverine structures used to catch fish. Indigenous people were the first to use fish weirs in North America. European Americans, who arrived later also used weirs.

In 2018, archaeologists of the Cape Porpoise Archaeological Alliance (CPAA) located two intertidal rock formations. CPAA archaeologists feel there is evidence that these rocks are the remains of a weir constructed by Wabanaki people. The Wabanaki are the Indigenous people who have inhabited Cape Porpoise and other parts of the northeast for thousands of years.

Archaeologists feel that these rocks were used to anchor a sectional weir of perishable material such as wood or reed that has not survived. The rocks and perishable materials together made the two fish weirs.

Why do we think these rocks are part of a Wabanaki fish weir and not a Historic period fish weir?

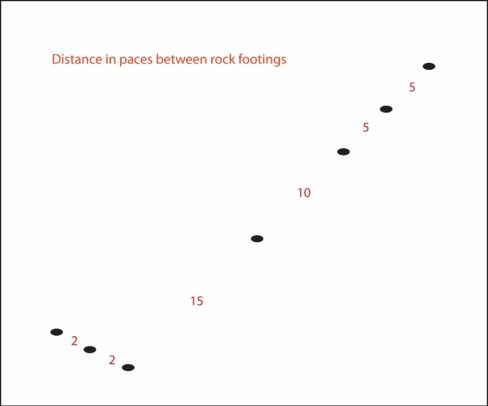

- The rocks of the Cape Porpoise weir have equal distances of multiples of five steps between them suggesting they were stepped off before being placed. This further suggests the rock formations were made by people and is not a natural geologic formation.

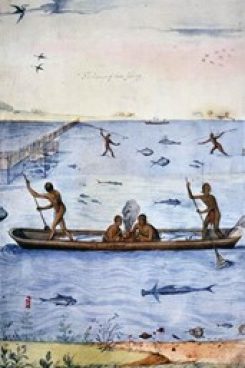

- The placement of the rocks in relation to the island’s shore is most like a weir illustrated in a 1585 painting by John White and not like salmon or sardine weirs used during the Historic period.

- Weirs come in a variety of sizes and shapes. The shape and size of the Cape Porpoise weirs are like the one shown in White’s painting. Notice the distinct 90 degree turns.

- Indigenous artifacts and the remains of a 700-year-old dugout canoe have been located near to the weir remains.

- Although weirs were widely used in the 19th and 20th centuries for commercial salmon and sardine fishing, they were mostly used northeast of Portland, Maine.

- Although commercial weirs in Maine were well documented through tax maps and photographs, there are no records of commercial weirs in Cape Porpoise.

History of Weirs in Southern Maine

Written records tell us that Captain John Smith fished in Cape Porpoise in the early 1600’s but he and his crew fished offshore from boats. During that time, Smith recorded that Indigenous “fished among the isles” similar to what is seen in White’s painting. In 1602, when traveling between Cape Cod and Cape Porpoise, English explorer John Brereton recorded that fish weirs were commonly used by Indigenous people.

After the 1600’s, the commercial fishing industry began using weirs. Sardine weirs were built along rocky shores, while salmon weirs ran perpendicular to the shore. These Historic salmon and sardine weir types were shaped differently than the one illustrated by White.

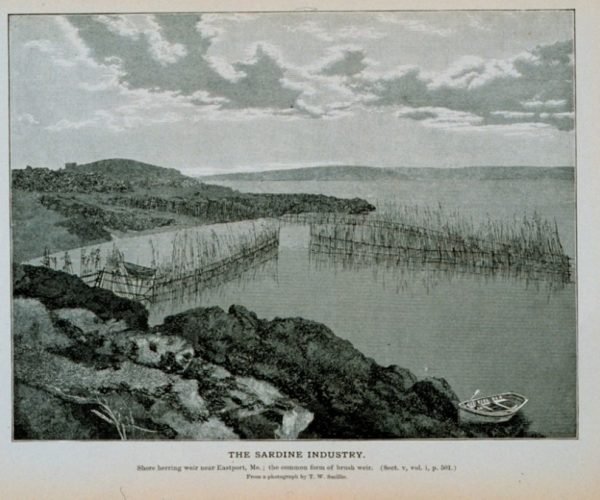

- This is a photograph of a commercial sardine weir taken by T.W. Smillie of the Smithsonian Institute around 1900

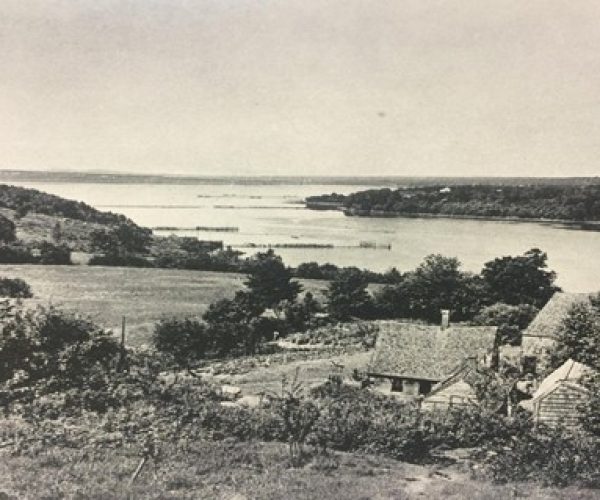

- This photograph taken by G. Brown Goode during the late 1800’s shows salmon weirs running perpendicular to the shore.

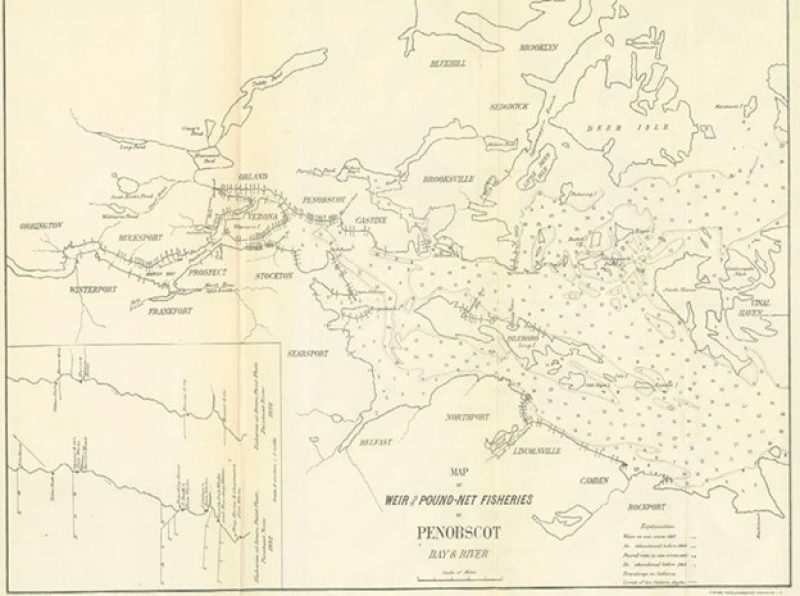

During the 1800’s and 1900’s, there were many commercial fish weirs documented in maps such as the one below. There are no known maps, photographs or records of weirs in Cape Porpoise.

Natural or Man-Made?

Our findings show that the rock formations located in Cape Porpoise were made by people and are not naturally geologic. The size, shape and geographic location of the Cape Porpoise weir are most like the one illustrated by John White in 1585 and are different in size and shape than Historic weirs. We therefore submit that the rock features located by CPAA archaeologists are the remains of a Precontact Wabanaki fish weir.